The Columbia River flowing through carved out basalt cliffs at Vantage Washington

This diary describes an Ice Age Floods Institute field trip that I took in September last year that explored some of the remnants of the ice age floods in the pacific Northwest that periodically burst from Glacial Lake Missoula and later from Lake Columbia over the last approximately one million years. This particular field trip covered the Central Columbia region, the Hanford Reach National Monument, White Bluffs, including the larger Pasco Basin. This diary covers just one segment of this huge flood area that is too large to describe in a single diary. I described the part that flooded the Walla Walla Valley previously and plan to cover other areas in the future.

Columbia Plateau and the Pasco Basin, South Central Washington State:

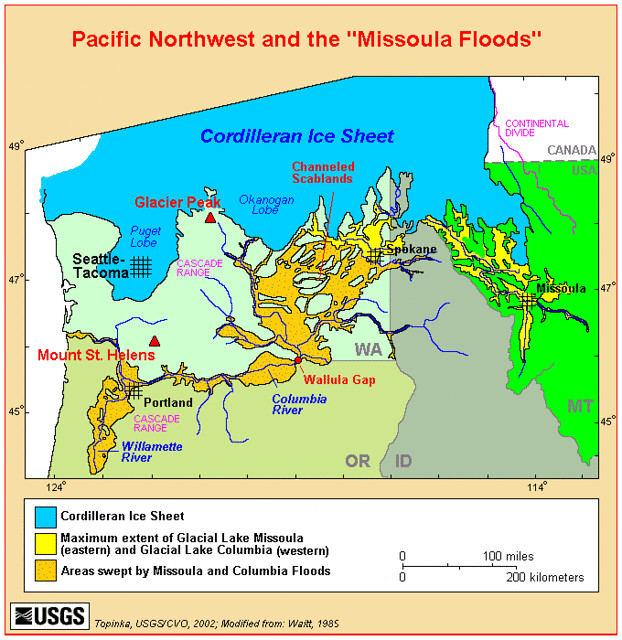

These enormous cataracts sculpted the terrain of central Washington State into what is now referred to as the “Channeled Scablands,” as they coursed through south central Washington and then on to the Columbia Gorge bordering with Oregon. The first of these wild cataracts poured through this area, perhaps a million years ago. Analyses show that that they began at least 780,000 years ago based on paleo-magnetic dating of their lower sedimentary deposits. Some suggest that they may have begun a million years ago with as many as 1,000 floods over time. During the most recent ice age there were perhaps 100 or so floods that occurred between 18,000 and 15,000 years ago as the Pleistocene epoch thawed to an end.

The immediate sources of these flood waters and their ice dams was the giant Corderillian Ice Sheet that covered western Canada, parts of Alaska, northern WA, Idaho, and northwest Montana. This ice sheet was confined on the east by the western slope of the Rocky Mountains. It could not top the continental divide. At its southern extent, there were three basic lobes: the Puget Lobe that carved out Puget Sound, the Okanagan Lobe in north central Washington that fed the Columbia River, and the Purcell Trench Lobe that formed the Glacial Lake Missoula ice dam and lake in Montana. The various floods initially flowed from Glacial Lake Missoula, across northern Idaho and down through central Washington’s Columbia plateau. The outburst waters coursed down the Columbia River drainage. Overflow flooded and raged down through the central basin carving the Channeled Scablands. Eventually these waters converged in south central WA where they were backed up by the constriction of Wallula Gap shown here, that funneled the Columbia River and the huge flow through a 3km wide cut in 1,000 foot high basalt walls.

As the water drained through this bottleneck, it continued down the Columbia River Gorge and on to the Pacific Ocean. Around present day Portland, it also backed up and formed temporary Lake Condon that flooded what is now the Willamette Valley in Oregon. Remnants of the floods are found in debris some 300 miles off shore. Due to the amount of global water bound up in ice sheets, the Pacific shore (sea level) was then 50 miles west of the present shoreline.

Behind Wallula Gap, the backed up floods formed temporary Lake Lewis that covered much of southwest Washington, leaving only a few hill tops above 1,200 feet peaking above the backwater. The Tri Cities (Kennewick, Pasco, Richland) and this central basin were under ~900 feet of water during the largest floods. At times floods backed up and flowed over the top of Wallula Gap shown above. Further, it backed up into nearby valleys such at the Yakima Valley to the west and the Walla Walla Valley to the east, both are now renowned wine grape growing regions.

Underlying the Columbia plateau that was carved by these floods was an enormous basaltic layer up to 2 miles thick. On top of the basalt was a sediment layer called The Ringold Formation consisting of deposits set down by ancient lakes and rivers. Topping it all were layers of silt, wind borne loess, and various deposits laid down by the floods.

Basalt cliffs along the Columbia R.

During the floods, this basin and adjacent areas were covered by temporary Lake Lewis with icebergs and flows loaded with rocks and debris that had been ferried from several hundred miles to the north and east. These floats were torn from the glacial dams and rafted with the flood waters. As the waters slowed and receded behind Wallula Gap, many of the bergs came to rest where they melted and deposited their payload.

The size and volume of these floods is difficult to comprehend. It is estimated that the larger floods each contained as much as half the volume of Lake Michigan, rampaging though and over the Columbia basin at speeds of up to 65 miles per hour and as much as 80 MPH down the Columbia Gorge. The power of such moving water is evident as it flowed over and through existing terrain while carving new channels, coulees, and troughs out of the basalt and sedimentary floors. A given flood along with backed up water of Lake Lewis lasted only a couple of weeks or so at a time before it was able to push its way through the gap and run on to the ocean.

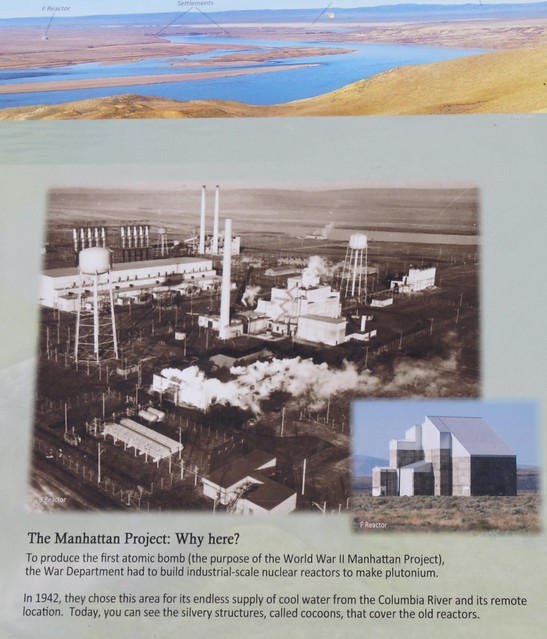

The Manhattan Project in the recent History of this basin

In the early 1940s, the Manhattan Project needed an isolated place with access to unlimited water to cool their nuclear reactors that would generate the plutonium for atomic bombs. The government chose a rather desolate area in south central Washington State along the Columbia River. Since 1943, The Hanford Nuclear Reservation has occupied a segment of this territory. It was here that the Manhattan Project scientists isolated the first plutonium in a volume sufficient to constitute the atomic bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki and that has kept the world in fear ever since.

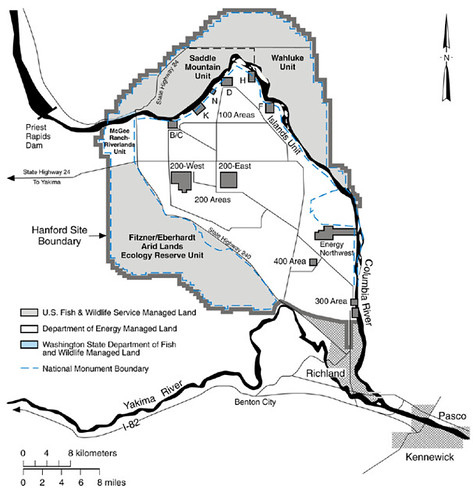

The Hanford Reservation as it has been called, is bounded by the Columbia River on the north and east sides, by Rattlesnake Mountain on the west, and Richland WA on the south. For years this area was off limits to the general public and much of it is still. However, restrictions have loosened and more of the reservation is accessible to the public allowing viewing of these ice age artifacts as well as the historic reactors. State Route 240 runs alongside the current restricted area.

This field trip then focused on the area around the Hanford reservation that includes the eastern slope of Rattlesnake Mt. which is under the federal protection of the Arid Lands Ecology Reserve, a unit of the Hanford Reach National Monument, managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Hanford Reach National Monument also includes land across the Columbia River to the north, including White Bluffs and the Saddle Mountains, and down the east side of the river across from the reservation. The main features we were there to observe were ice-rafted erratic boulders and Bergmounds as well as other local features that directed the floods and features of the terrain created by the floods’ immense hydraulic forces.

The first stop on the field trip was to view an ice-rafted erratic boulder that was brought down with one of the floods. It consists of a single block of “Granodiorite,” and is located next to a vineyard and a trio of wineries in Richland, WA. This granite-like rock is medium sized and probably came from either northern WA or from the Purcell Trench in Northern Idaho. Granodiorite has a place in human history as well including being the rock of the Rosetta Stone. Further, the Plymouth Rock of Pilgrims’ fame was a glacial erratic of granodiorite.

Granodiorite Erratic Boulder. Note vineyards in the background

Granitic rocks are by far the most frequent erratics found in this area (75%), followed by quartzite, and diorite. A small number of basalt rocks are also found, probably picked up by glaciations in the Okanogan lobe in the Northern part of the state.

Our next stop was at Badger Coulee where we were able to see various “rhythmites” (layers of sediment) from successive floods. This location was of particular interest as among the layers of sediment were two separate layers of volcanic ash deposited by eruptions of Mt. St. Helens, approximately 16,000 years ago. Also of interest was that this coulee had once been the route of the Yakima River. However, successive flood deposits plugged it such that the river was eventually diverted north to its present course where it enters the Columbia River just south of Richland.

White layers of Mt. St. Helens’ ash from 16,000 year old eruptions

The next leg took us along State Route 240 that runs from Richland, north to the Vernita Bridge where it crosses over the Columbia River. This highway now skirts the edge of the Hanford reservation which lies to the east. On the west side of the road we see Rattlesnake Mountain rising to a height of 3,526 feet.

Sign on barbed wire fence surrounding the DOE nuclear reservation.

The north east side of Rattlesnake Mountain is now designated as part of the Hanford Reach National Monument. Much of the rest of the trip is within the Monument’s boundaries.

The Hanford nuclear Project (DOE) in the center, white, surrounded the Hanford Reach National Monument in gray.

Rattlesnake Mt. and Hanford Reach National Monument.

The Yakama Nation referred to Rattlesnake Mountain as Lalíik, meaning “land above the water.” Some historians speculate that the origin of the name Lalíik refers to the inundation of the Columbia River Plateau during the Missoula Floods, as Rattlesnake was one of the few mountains in the area not completely inundated by flood waters reaching heights of 1,200 ft (366 m).

The greatest concentration of erratic boulders, erratic clusters, and Bergmounds are found along the north slope of Rattlesnake Mountain. Bjornstad found over 1,200 of these deposits along just a portion of this slope. Many more are buried out of sight beneath the sediment deposits from later floods. The mountain was a sort of backwater where some of the icebergs were grounded as the lake level dropped. Here they melted and deposited their cargo of rocks and debris that they had rafted from as far away as Montana and Canada.

Bergmounds were formed where icebergs deposited a conglomerate of contents including boulders, gravel, and silt leaving isolated mounds.

Bergmound (the dark mound) at the foot of Rattlesnake Mt.

Bergmount in the foreground, erratics on the left and right center, visible from HWY 240

Moving along SR 240, north toward the Columbia River we saw several other flood features:

As the flood pushed through central WA, much of it followed the Columbia River channels while other parts just flooded overland carving new paths. To the Northwest, there was a constriction of the Columbia’s flow called Sentinel Gap that slowed the water behind it and sent rapid flowing streams through it.

Sentinel Gap constricted the Columbia River and flood waters

The sentinel up close rising above west side of the Columbia River

The east side of Sentinel Gap and part of the Saddle Mountains

Downstream from Sentinel Gap, the rushing waters slowed again as they spread out, and deposited a large gravel bar as seen below that was built up over successive floods. Below in the center ground is the Priest Rapids Bar with the Saddle Mountains in the background. The river runs along where the trees are.

Turning to the northeast now, we can see some of earliest and continuing structures of the Hanford nuclear reservation. You can see how the river wraps around with the various large concrete structures that once housed active nuclear reactors. Most are now “cocooned” or mothballed as they sit cooling down.

White Bluffs area nuclear reactors along the Columbia River

B reactor where some of the plutonium for the first atomic bombs was made. It sits

secured at rest

White Bluffs and Saddle mountains in the background. Columbia R. runs under the bluffs

The area is called the White Bluffs for the white bluffs across the river. This was a small farming community and a fishing camp of the Wanapum Indians prior to the Manhattan project. In 1943 all inhabitants were relocated when the government took over and built the reactors. These bluffs were eroded by the floods and by the Columbia river over millennia. They consist of sedimentary deposits called the Ringold Formation, laid down by ancient rivers and lakes that covered this area millions of years ago.

Moving from this vantage point we continued across the river and drove along above the bluffs, all of which is part of the Hanford Reach National Monument. Below we can see this area, the river and the bluffs from a different perspective at the White Bluffs Overlook.

Columbia River reach, flowing freely under White Bluffs

Looking West from the White Bluffs Lookout, we can see the Saddle Mts. in the background and the nuclear operation which includes the Waste Treatment program in which radioactive materials are being vitrified for long term storage. The foreground shows a large landslide down toward the river, probably from some 14,000 to 15,000 years ago.

This part of the river is the only free flowing (non dam impeded or backed up) part of the Columbia River today. The area along the banks and these islands are part of the Monument and are wildlife preserves – no humans allowed.

It is an unfortunately inevitability that some of the stored radioactive waste has escaped its storage tanks and is beginning to seep toward the Columbia River. Major efforts to identify and control this seepage are underway and have been for decades. I hope they hurry.

I have noted that only some of the water followed south down the Columbia River route from the breached ice dams. Large torrents also flowed overland carving channels such as the Channeled Scablands and the Drumheller Channels out of the underlying basalt. (Be sure to watch the drone fly-over videos at this web site). When these waters ran up against the Saddle Mountains on the north, just south of present day Othello, WA, they were parted. Some went west toward the Columbia River and eventually found their way through the Sentinel Gap. Other waters were deflected around the east end of the Saddle Mountains.

Parting of the waters around this promontory

The promontory in the middle of the above photo split the onrushing flood from the north, sending some to the west toward Sentinel Gap and some to the east through Othello Channel and to the east side of the Pasco Basin. Waters taking the latter route had less scouring power and resulted in creating parallel and relatively shallow coulees: the Ringold and Koontz. These coulees ran for 12 miles and created the long streamlined sedimentary hill seen below, now surrounded by irrigated farmland.

Streamlined Ringold Hill separates Ringold from Koontz coulee

From there the field trip motored on to a different but related feature of the floods: a Mammoth dig near Kennewick. The Columbian Mammoth being excavated is buried in flood sediment which might have caused its demise or it might have died up stream and been rafted to its present site by some of the later floods. The mammoth bones have been radiocarbon dated to ~ 17,449 years ago, well within the time frame of the latter floods. But that is a story for a subsequent diary.

Addendum:

Although there are many kinds of wild flowers throughout this area in the Spring and Summer, the majority of flora here is of the sort that needs little water in this semi-arid desert. Ubiquitous are various species of sagebrush, Rabbitbrush, and tumbleweeds galore.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Bruce Bjornstad and Gary Kleinknecht, our able tour leaders for their expert knowledge and willingness to share it with all.

References and web sites

• Bjornstad, Bruce N. (2006). On the Trail of the Ice-age Floods: Guide to the Mid-Columbia Basin, Keokee, Sandpoint Idaho.

• Bjornstad, Bruce N. and E.P. Kiver, (2012). On the Trail of the Ice-age Floods: The Northern Reaches, Keokee, Sandpoint Idaho

• Bjornstad, Bruce N., Kleinknecht, Gary, & Last, George, (2014). Ice Age Floods Through the Mid-Columbia Region. Ice Age Floods Institute Annual Meeting Field Trip, September 13, 2014

• Bjornstad, Bruce N. (2014), Ice-rafted Erratics and Bergmounds from the Pleistocene outburst Floods, Rattlesnake Mountain, Washington. Quaternary Science Journal, V. 63 (1), 44-59.

• Web sites

o http://www.iceagefloodsinstitute.org/index.html

o http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Hanford_Reach/Geology/Ice_Age_Floods.html

o http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Hanford_Reach/

o http://www.nps.gov/iceagefloods/

o http://www.hugefloods.com/

o http://www.coyotecanyonmammothsite.org/index.html

http://www.brucebjornstad.com/

http://www.murray.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/newsreleases?ID=32c2cf4b-9f79-44bf-98d1-0b0a9ebaefc8

This is part 2 of the Ice Age Floods Series and focuses on mid Columbia Basin floods and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation that sits within it. If you find this at all interesting, I highly recommend that you check out the links in the diary. They show some very spectacular views, including aerial views of this area that really demonstrate the vastness and power of these floods.

I must have missed this when it first went up. Wow, what a fascinating history. Many thanks. And the photos really make it all come home.