Late October, 2015

North Cascades Mountains

Washington State

A trip in late October took me over the North Cascades Highway, through the North Cascades National Park and to Chelan where I met my two brothers for our annual three day exploration of the region’s natural wonders. We traveled to the Grand Coulee and its Dam along with other remarkable remnants of the giant Ice sheets that carved out large segments of Washington State. At Chelan, we boarded a foot ferry for a 100 mile round trip up Lake Chelan to the isolated village of Stehekin. Finally I returned home to Bellingham via Stevens Pass to complete the North Cascades Highway Loop. I took too many photos for a single diary so I’ll break the trip into segments: the North Cascades National Park, Lake Chelan, and the Grand Coulee. All along the way the residue of the summer’s massive forest fires was prominent.

The North Cascades Highway follows State Route 20, that stretches from the Olympic Peninsula near Discovery Bay, across Puget Sound over ferry routes, up and over the Cascade Mountains, and terminates at the Idaho border. Due to the height of the highway (Washington Pass at 5,477 feet), along with the pacific moisture and precipitation, it is closed about five months of the year. The Highway typically opens in April and closes in November although there have been a drought years when it did not close at all. The mountains are currently getting good snow so it is likely to close soon.

The North Cascades national Park and the Cascades Loop Highway

Once over the mountains and the Columbia River is reached, the Cascade Loop follows the river south on US 97 to Wenatchee where it meets U.S. Highway 2 going west and over Stevens Pass to return to Western Washington and complete the loop. This North Cascades route was originally the corridor used by local Native American tribes as a trading route from Washington’s Eastern Plateau country to the Pacific Coast more than 9,600 years ago. It opened as a cross state highway in 1972 as the first National Scenic Highway in the United States, after over 100 years of planning. Appropriately I think, it has been called: “The Most Beautiful Mountain Highway in the State of Washington.” In addition to the monster mountains, rivers, and streams, the North Cascades National Park boasts 1,600 plant species, more than any other National Park. Of course all the water helps out. The trip began traveling east following the Skagit River up into the mountains, soon to enter North Cascades National Park. Along the lower part of this route is some of the best eagle watching territory in the winter following the salmon spawn.

Entering the Park the mountains loom over the terrain but often there are power lines in the foreground that remind us that we are still in the civilized world – we need electricity.

Mountains loom over power lines that are part of the Seattle City Light Hydroelectric project Driving toward the Park’s Visitor’s Center, the scarred and blackened trees and undergrowth from the summer’s fires were startlingly apparent. The first fire remnants that I encountered on this trip were from the Goodell fire that closed the entrance to the Park, the visitor Center, the community of Newhalem, and the dams that make up the Skagit River Hydroelectric Project, run by Seattle City Light. The following photos show some of the fire damage, even getting down to the highway.

This hydroelectric project has three dams on the upper reaches of the Skagit River, all within the National Park boundaries. The first is Gorge Dam, built in 1924. The second, Diablo Dam was built in the 1930. At 389 feet, Diablo was the highest dam in the world for six years. The third is Ross Dam and its reservoir, Ross Lake that backs up water 25 miles north protruding well into Canada. These three dams were also closed and their associated personnel were evacuated during the August fire.

Diablo Dam and its emerald waters, Driving across the dam.

Moving on up the pass there are many spectacular sights but the most imposing and majestic rise above Washington Pass which sits at 5,477 feet. Towering above the Pass is Liberty Bell mountain which rises another 2,300 feet. To the South of Liberty Bell are two spires, called Early Winters Spires, both seen here cloaked in the clouds. (I recommend that you check the links here for some magnificent views of these peaks without the mist and clouds.)

Liberty Bell Mountain and Early Winters Spires

The National Park itself boasts over 300 glaciers, more than any park in the contiguous 48 states. Further, more than half the glaciers in the lower 48 states are concentrated within this North Cascades wilderness region.

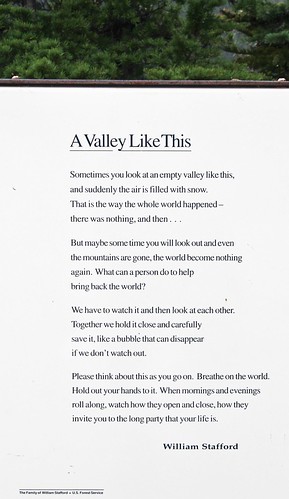

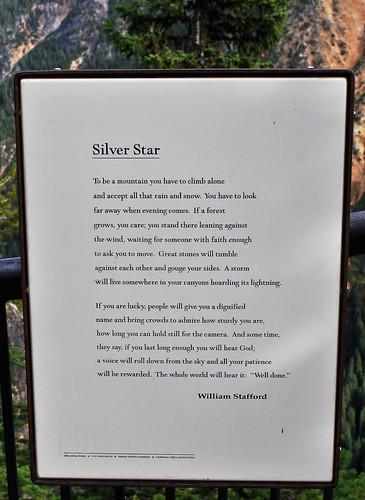

The US Forest Service has posted poems at various lookout points over the pass. The forest service commissioned William Stafford to write these poems specifically to commemorate this awe inspiring scenery of the North Cascades.

The spring 2006 issue of this newsletter featured a cover story titled “The Methow River Poems: More Than A Roadside Attraction.” It told how in 1992, a year before his death, William Stafford was commissioned by the Forest Service to provide a series of poems that fit the high Cascades landscape and could be “posted” at various points along the river highway. This collection of poems turned out to be the last complete body of work that William Stafford produced, and the one he infused with perhaps his greatest passion.

North Cascades Highway descending from Washington Pass

From Washington Pass the highway descends rapidly into the Methow Valley where it follows the Methow River to the Columbia. Reaching the Columbia, the North Cascades Loop joins US 97 heading South to Wenatchee where it joins US 2 heading West over Stevens Pass. Stevens’ Pass is not as high as The North Cascades, rising to just over 4,000 feet. The East side of the pass follows the Wenatchee River up into the Mountains. Here are a few photos from the trip back across the Cascades to Western Washington. As you will see, the rain followed over the pass too.

River with fall color accents in the rain

The Wenatchee River as the sun peaked out for few seconds

Fall color across a dam

The Cascade Mountains’ Origins:

These mountains are fairly old and are composed of a potpourri of rock sources including some from each basic rock origin: igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic.

The North Cascades record at least 400 million years … in the history of this restless Earth-time, enough to have collected a jumble of different rocks. The range is a geologic mosaic made up of volcanic island arcs, deep ocean sediments, basaltic ocean floor, parts of old continents, submarine fans, and even pieces of the deep subcrustal mantle of the earth. The disparate pieces of the North Cascade mosaic were born far from one another but subsequently drifted together, carried along by the ever-moving tectonic plates that make up the Earth’s outer shell. Over time, the moving plates eventually beached the various pieces of the mosaic at a place we now call western Washington.

More recently, the Juan de Fuca plate pushing under the North American plate gives rise to the range and to its volcanic activity as part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. There are 14 volcanoes in the Cascade Range stretching from Mt. Garibaldi in BC to Mt. Lassen in northern CA. Many are still volcanically active including Mt. St. Helens, Mt. Baker, Glacier Peak, and Mt. Rainier for examples. The majority of the rocks making up this range are granitic in nature including tonalite and granodiorite.

Here is a post describing my recent trip across the North Cascades Mountains in Washington State. For whatever reasons, I struggled with the formatting so please forgive its awkwardness and pass on any hints you might have to deal with issue that you see. Enjoy the photos.

Thanks RonK. I love the surprise of the poetry.

The valley around us is deep

Thank you for sharing your trip with us, RonK!

(formatting looks fine to me)

Thanks for the Editor’s choice JanF. It finally turned out OK but with all the photos and lots of links, it was a bit challenging at times. I’ll need to get more systematic at moving parts from Kos and plan ahead better.

I think the trick is to compose the diary elsewhere: the DK editor is just not going to let you get the html you need to crosspost successfully. I did some experimenting on the beta site a few weeks ago … it simply won’t move images well. You can compose in a Word document, for example, or on a WordPress blog (I think you have one, right?) and then move it to DK and here. I am not a fan of WYSIWYG … I don’t mind composing in that mode (View Mode here, I think) but I really need a Preview button to ground myself. But I am old!

Me too. I need a preview button. The text from the visual mode, even after saving, was often different from the preview on WP. That threw me for a while until I just trusted the Preview as being the final look.

Even preview has some quirks on certain sites. On the old Moose, the final diary would often look different, I think because the published font was different from the composition font.

But trusting WYSIWYG has never been a good idea.

What do you think about this story about the “long overdue” Cascadia subduction area earthquake?

When will a massive earthquake, tsunami hit the Pacific Northwest?

Yikes!

This is all too real JanF. We’ve known about it for some time but recently two major stories have brought it back to the forefront. Also, much of the recent writing on it comes following a report of a 13 year long study by NOAA and Oregon State University geologists that has been taking core samples all along the various fault lines to identify previous earthquakes. On Thursday, I am going to a talk at our City Club where the lead researcher, Chris Goldfinger will discuss this and its relationship to our specific area. Interesting but scary. Our old house will not hold up well to a big quake but it would be hugely expensive to retrofit for protection. I hope to learn more soon.