We left off in Part 1 at Celilo Falls and The Dalles Dam, the last dam before the river meets the ocean. This remaining portion of the river’s journey is also spectacular although the landscape takes on a different character. After leaving the Canadian Rockies, the terrain along the river has been relatively barren, semi-arid plateau with the river cutting deep canyons through ancient basalt flows. The vegetation is largely shrubs and grasses with some pine where it approaches the mountains.

Leaving The Dalles, the arid brown landscape of the Columbia Plateau gives way to greens of a more marine climate as it heads toward the ocean. This change is exemplified by the lushness and pastoral beauty of the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area.

The Columbia Gorge and Crown Point with Vistahouse above the River (wikipedia)

This National Scenic Area is the largest in the U.S. and boasts 75 waterfalls, the largest concentration in the US, and 24 State Parks and Recreation Areas. In addition to the scenery and recreation areas of the immediate environment, the distance offers views of two snow topped mountains, Mt. Hood in Oregon, and Mr. Adams in Washington. Just 40 miles north of the gorge one could also see the snowy top of Mt. St. Helens, until it blew its top in 1980.

Multnomah falls, overlooking the River. The falls drops in two major steps,

split into an upper falls of 542 feet and a lower falls of 69 feet. Photo by Mitch Schreiber

Moving on downstream the Columbia collects the waters of the Willamette River, the last large river to join up before meeting the ocean. At this conjunction the river passes Portland on the Oregon Side and Vancouver on the Washington side. From the Portland — Vancouver area, the river’s course turns toward the northwest for about 45 miles before heading west again on the final 50 mile leg of its journey.

Closer now to the river’s mouth, it continues to slow and widen in places with numerous islands breaking up the main channel and giving a braided river appearance. Note that its surroundings are now green forested hills and farm land.

The Columbia River wending its way around multiple islands as it nears Astoria, OR

Astoria and the Mouth of the Columbia

Approaching Historic Astoria, the river widens to over four miles where it is spanned by the Astoria-Megler Bridge. Now its flow is no longer affected by man-made dams but rather by the push of its own current and the push back of the ocean’s tidal movement.

Astoria-Megler Bridge from Oregon to Washington in the distance

Astoria, originally Fort Astoria, was built as a fur trading post by the John Jacob Astoria American Fur Company in 1811. The fort was built just a few miles from where Lewis and Clark built Fort Clatsop only five years earlier (1805-1806). Fort Astoria was the first permanent U.S. settlement on the Pacific coast and had the first U.S. post office west of the Rockies.

The U.S. Coast Guard maintains a large presence here as Astoria it is a deep water port as are others up to the Portland area. These ports ship agricultural products that come down river from the Eastern Washington’s Columbia Plateau ( irrigated by the Grand Coulee and other Dams) and Oregon’s Willamette Valley and its eastern farmlands. Many agricultural products are barged from up the Snake River. Also shipped from here are many manufactured products including aluminum made with the abundant electricity from the numerous hydroelectric dams on the river.

The Columbia River Maritime Museum on the Astoria waterfront

In reference to its 200 year maritime history Astoria maintains a Columbia River Maritime Museum.

..

..

One of my favorites is the foot operated fog horn.

Coast Guard Ship and the Light Ship Columbia, a National Historic Landmark, moored at the Museum.

Japanese fishing boat that floated across the Pacific to Oregon after the tsunami of 2013.

The mouth of the River and the Columbia bar

Although many had tried, the first known Euroamerican sailing ship actually to cross the bar and enter the River was the Columbia Rediviva, captained by an American merchant trader, Robert Gray on May 11, 1792 — hence the river’s name “Columbia” after his ship. The presence of a river here had been rumored by many and thought possibly to be the fabled Northwest Passage. Of course it was known by the Indians for thousands of years. Without a formal English name until this point, it had been referred to as the “The River of the West,” “The Great River of the West,” and allegedly “Great River Ourigan” (Oregon). After gaining entrance to the river, Captain Gray and his crew anchored in Baker Bay to trade goods such as furs with the Chinook Indians who populated the region. Today, Illwaco WA, the last town on the river and a timber and fishing village is situated in Baker Bay. (see Baker Bay in the map below.)

Most rivers entering the sea develop sand bars of sediment that create hazardous shoals along with breaking waves and unpredictable currents when tide, river current, and storm collide. But few if any, are quite like the Columbia Bar for several reasons. Firstly there are near constant onshore winds that push waves and swells against the oncoming river flow which is described as “like a fire hose” gushing into the sea. Secondly, unlike many other rivers the Columbia does not have a delta that can disperse the river waters over several channels. Thirdly, these hazardous conditions are made worse by rapidly changing weather conditions and direction of swells that can go from relatively calm to life threatening in as little as five minutes. Historically this bar itself was treacherous as well due to constantly shifting sand bars across the opening, precluding effective use of charts to find a natural channel.

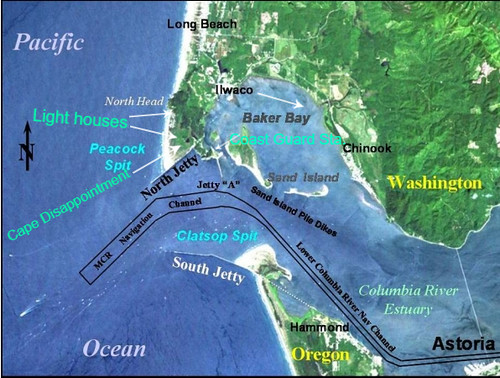

Mouth of the Columbia, Cape Disappointment and shipping channel

Fortunately, safety measures now assist ships getting through the bar. There is now a well marked and maintained channel dredged to 55 feet deep and 600 feet wide as it comes over the bar. Secondly, all vessels engaged in foreign trade (about 3,600 a year) are required to take on board prior to entering the mouth, a Licensed River Pilot to maneuver the ship through the bar.

Still many boats are either driven aground or are capsized by the weather and water. Historically this area has been the most hazardous part of the “Graveyard of the Pacific,” which has claimed about 2,000 ships since 1792.

Below is one of the lost ships, the four mast steel bark, Peter Iredale as it was after it ran aground on Clatsop spit, near Fort Stevens in 1906. All 27 crew members were rescued.

The wreck of the Peter Iredale is shown in this photograph,

taken by Portland photographer Leo Simon on November 13, 1906,

The skeletal remains of the Peter Iredale, November 2017,

111 years after its grounding. More of the ship’s structure is visible at low tide.

The U.S. Coast Guard, not surprisingly has a large installation here at the bar. Given that this bar arguably has the roughest estuary waters in the country and maybe the world on a regular basis, it is the rough water training grounds for the US Coast Guard’s National Motor Lifeboat School.

This Cape Disappointment Coast Guard station has nine search and rescue boats, three of which are capable of re-righting themselves when rolled over by breaking waves. This Station is relatively busy with their rescue mission. In 2015 they had 162 calls to action which saved 97 lives.

Cape Disappointment Coast Guard Station rescue boats (see them in action in the video below)

This video demonstrates the type of water that is typical of the Columbia Bar. I was told that I had just missed a training session the day before I visited the Cape in November. It was a day like that shown in the video.

There are three man-made jetties that aid ships and pleasure craft on crossing the bar. The South Side jetty extends 2.5 miles into the sea and the one on the North extends 6.6 miles out. A third smaller jetty is inside the bar, Jetty “A” on the chart. These jetties were built in 1885 and continue to require regular upgrading and repair as they are mightily hammered by the waves.

South Jetty extending 2.5 mile out. Freighter (top left) about

to enter the channel. Note sand build up behind the jetty on the right

The jetties’ function is to help maintain the depth and orientation of the navigation channel by reducing the shifting sediment of the sand bars. However, the jetties also change the currents which results in a redistribution of the sediments that build up behind them. Since the north jetty was completed in 1917, 600 acres of new land have built up behind it as seen in the photo below.

North jetty with new land behind it, becoming forested.

Cape Disappointment marks the North side of the River’s mouth. This prominent cape was named for the disappointment of one British fur trader, Capt. John Meares. Meares, like many other explorers and traders in the late 1700s, looked for but failed to find the entrance of the Columbia River. Little did he know that he almost made it in 1788. His ship was held at bay just north of the mouth by intense storm activity and swells.

It was fortunate for the young United States that Meares turned around just a couple of miles short of finding the opening. That left its discovery to Captain Robert Gray whose recording of his entry in May 11, 1792, and his trading with the local Indians, along with Lewis and Clark’s later documentation of their own arrival from up river, as support for the U.S. claim to the new territory.

Aside from the Coast Guard station, the Cape is home to two light houses. The first one was built on the Cape in 1856 at the entrance of the river. However, it was set back from the sea a bit and ship traffic coming from the north could not see it well. To remedy that a second one was built in 1897 a couple of miles to the north on North Head which is shown in the opening photo. Below is the Cape Disappointment Lighthouse.

Cape Disappointment Lighthouse, overlooking the mouth of the Columbia River.

Nasty November weather day.

As Cape Disappointment is the site of much northwest history, there is an Interpretative Center/museum as part the Cape Disappointment State Park, overlooking the point. It was here that Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery finished their 1,400 mile journey from Missouri in November 1805. They first landed on the northern shore (Washington side), and were elated when as they had finally reached the end of their historic journey and on 7 November,1805, Clark wrote:

Great joy in camp we are in View of the Ocian, this great Pacific Octean which we been So long anxious to See. and the roreing or noise made by the waves brakeing on the rockey Shores (as I Suppose) may be heard distictly.

Their welcoming weather however was less than hospitable.

In November, 2017 I visited this area on both sides of the river’s mouth. I arrived at the mouth of the Columbia at the same time of the year that the Corps did – November 8 – 9th and like on their arrival, I was greeted by one of the trademark massive Pacific storms. This area is such that it takes your breath away with its grandeur and then slaps you in the face with its elements. And so it was for me as it was with the Corps 212 years before.

The Corps’ initial elation did not last long as they were miserable from a torrential Pacific storm that pinned them down with driving rain and fog for 6 days before they could get out of their camp. At this point their deerskin clothing was in tatters and rotting off. On finally being able to leave this camp and head the few miles to the Cape itself, Clark referred to this camp as “this dismal nitch,” which is still on the maps. Next, they set up “Station Camp” on a “Butifull sand beech” where they stayed for 9 days exploring the cape and the mouth of the river before deciding to move and set up a winter camp. They voted (everyone had an equal vote, even the slave), to cross the river to the south side (now Oregon) as the local Chinook Indians told them that elk were plentiful there.

They called their winter camp, Fort Clatsop after the local Indians who inhabited the southern side. The fort was only about four miles from what just five years later was to become Fort Astoria.

Replica of Fort Clatsop on the original site.

Today there is a replica of Fort Clatsop along with another bronze statue of Sacagawea.

Another Sacagawea bronze just out side of Fort Clatsop, shown as she is typical portrayed,

with her baby, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau on her back.

And so ends our journey down the rolling waters of the Columbia River from its humble beginnings in the Canadian Rocky Mountains, through the basalt of the Columbia Plateau, through the Columbia Gorge and to the Pacific Ocean along with a taste of the history, both ancient and contemporary.

Thanks to all for coming along. I Hope you enjoyed the ride as much as I have.

Well, here is the final leg of the Columbia River trek. I hope you all enjoy this little vicarious trip down the river.

Thanks, RonK! Beautiful images – I am ready to visit!!

Thanks JanF, Come on out. We’re going to be here for the duration.

{{{RonK}}} – very much enjoyed the vicarious trip. Probably considerably more than I would have an actual one. LOL. The scenery is beautiful and yes I’d love to see it in person but the conditions for getting there are a bit much for me. Thank you for so beautifully detailing the beautiful area. moar {{{HUGS}}}

Thanks Bfitz. It is a long way out here and anymore, it is getting more and more difficult to hike into these places. I’m going to have to do more exploration while I still can. I’ll report back.