Modjeska Monteith was raised to be an activist, although it’s doubtful her parents would have phrased it that way. Her father, a master brick mason, and her mother, a schoolteacher who only quit teaching when Modjeska was born, were affluent by the standards of the day; their financial independence enabled them to stress the importance of racial pride, Christian mission, community service, and respect for education. Her father, the son of a white lawyer and his domestic servant (and a former slave), did not want his family to live subservient to the white world and emphasized the importance of supporting one’s own people. He kept pictures of famous black people in the home, and he made sure his family reached out to those neighbors who had less. Through their church, they often visited and cared for the ill or the desperately poor. The family supported black-owned businesses and were even part owners of a black-owned grocery store. Without realizing it, her upbringing was preparing Modjeska to be one of the “talented tenth.”

She attended college and after her graduation in 1921, she became a schoolteacher. It was only when she married Andrew Simkins in 1929 that she quit teaching; a decision forced upon her by the policy that married women were not allowed to teach in the Columbia SC school system. Her husband had been widowed twice before and had five children, and he never asked Modjeska to stay home as wife and mother. He, too, was a successful businessman, so they had the means to hire a housekeeper and have a live-in relative who helped raise their children. This prosperity enabled Ms. Simkins to pursue her commitment to public service by working in public health. In 1931,she became the Director of Negro Work for the South Carolina Tuberculosis Association, where her primary responsibility was fundraising in the black community and health education. With the start of the Depression, this was a daunting task, but Modjeska tackled it fearlessly. She would frequent gambling halls and churches; middle-class black organizations and tenant farms; mills and fields. She organized tuberculosis testing, wrote and published a newsletter, and organized state meetings of black leaders.

It was these contacts that led her to attend an initial organizing meeting for the purpose of starting a SC NAACP state organization. Her early interest, as well as her involvement with the Columbia NAACP branch led to her election as state secretary in 1941. It was also this involvement that led to her losing her job with the Tuberculosis Association. She was pressured to sever her ties with the NAACP by the white board of the association, and she made her choice.

I couldn’t divorce my interest in civil rights from my dedication to trying to solve these health problems. My boss sensed it, and she said that I would have to leave off some of these activities. And my answer was that I’d rather see a person die and go to hell with tuberculosis than to be treated how some of my people were treated. Although I was not fired, my position became untenable and we parted ways.

As quoted in “Modjeska Simkins and the NAACP, Barbara A. Woods

Her involvement with the SC NAACP came at a crucial time. The South Carolina Conference was pursuing equal rights through the courts, first with a fight for the equalization of teachers’ salaries (which was won) and next with a case to eliminate “white primaries,” where only whites were allowed to vote in primary elections. This case, Elmore v Rice, went before the Supreme Court and was won in 1947, but the Democratic Party in South Carolina came up with new rules for party participation, e.g. affirming one’s belief in the separation of the races and upholding the belief in states’ rights. Another court case became necessary, Brown v Baskins, in order to obtain full voting rights in 1948. Ms. Simkins was involved in these cases as an observer and advisor to the national NAACP lawyers, including NAACP Special Counsel Thurgood Marshall, since she was more familiar with the details of the original SC cases.

The SC NAACP determined that their next case would be about receiving bus transportation for black students, but the strategy slowly evolved. Rather than just tackle providing buses for black children, the SC NAACP decided to pursue equalizing the schools themselves. This test case, Briggs v Elliot, was filed in the federal District Court in 1950, but one of the federal judges, J. Waties Waring, let it privately be known to Thurgood Marshall that the NAACP needed to stop fighting within the confines of Plessy and instead fight for full desegregation.

Thurgood told me…[that] Waring said, ‘I will not try another separate but equal case. When you get ready to make a frontal attack on segregation in the schools, then I’ll be ready to try the case.’

Ibid.

(A video about this can also be found here: Modjeska Simkins on Education) For the purposes of the test case, 20 plaintiffs would be required, and this is where Simkins played a critical role. Just signing on as a plaintiff would result in severe economic reprisals; it was known that in all likelihood, plaintiffs would lose their jobs, be evicted from their homes or tenant farms, and have their credit cut off.

The Briggses were not the only petitioners who suffered. Bo Stukes was let go at his garage, and James Brown was fired as a driver-salesman for Esso, though his boss commended him for never having come up a penny short in ten years on the job. Teachers got fired, Negroes had great trouble getting their cotton ginned that harvest season, and Mrs. Maisie Solomon not only go thrown out of her job at the motel but also tossed of the land her family rented and had to take rapid refuge with other blacks.

Ibid.

Ms. Simkins previous experience as a fundraiser, as well as her brother’s ownership of a bank, enabled her to help secure funding for those in dire straits. When the case was heard before a three-judge panel at the District Court (with Waring as one of the three), the decision came down 2-1 in favor of the school district. This defeat set up an NAACP appeal to the Supreme Court, along with four other cases. The Supreme Court agreed to group the cases, and the case argued before the court became known as Brown v Board of Education.

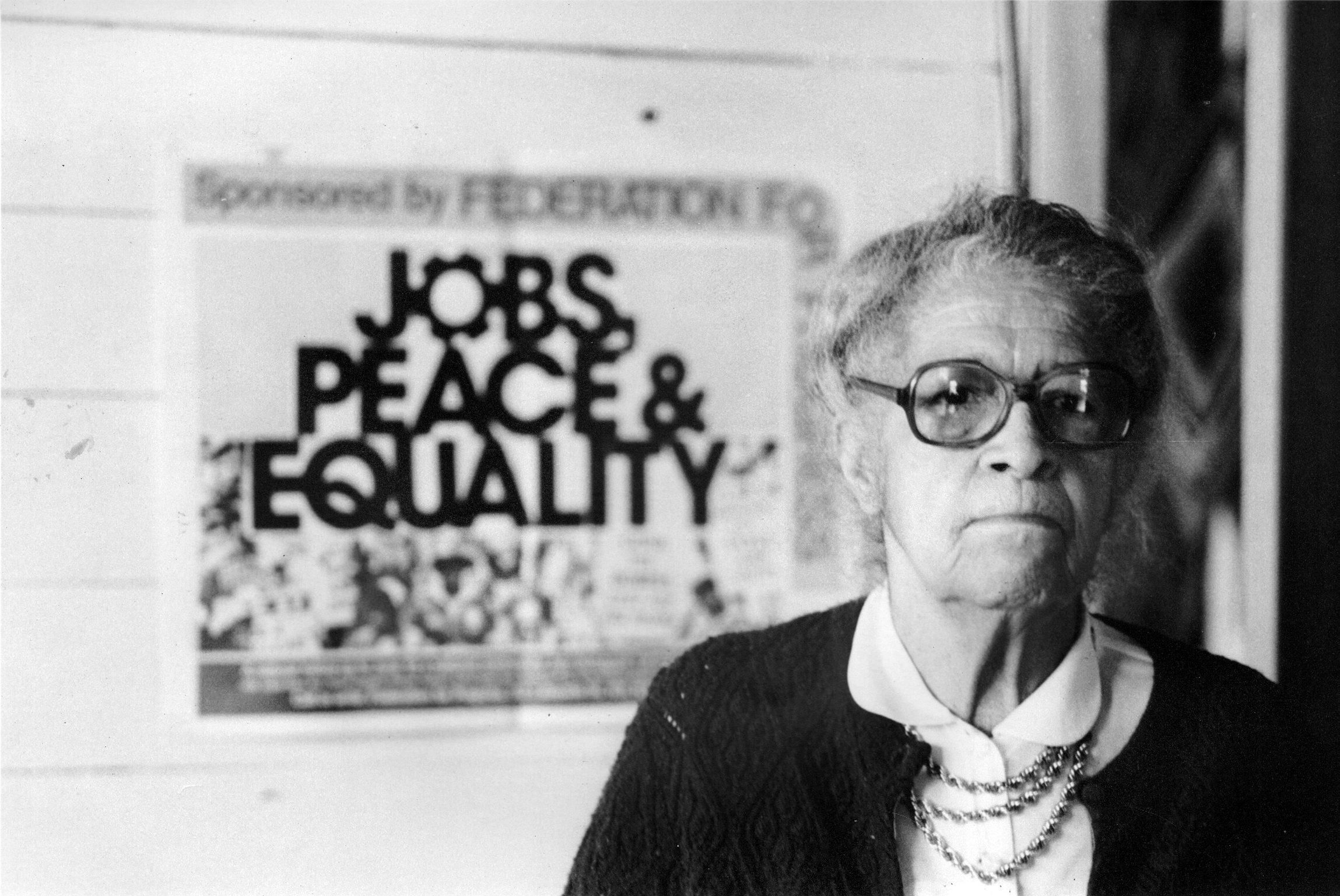

Ms. Simkins continued as secretary for the SC NAACP until 1957, when she her name was not included by the Nominating Committee. It was the height of the Red Scare, and because Modjeska had friendships with members of the American Communist Party, it is plausible, although not overtly stated, that the NAACP wanted to avoid bringing unwanted scrutiny from the HUAC. She continued to pay her membership each year, but never again worked as a paid worker or volunteer for the NAACP. In her later years, she worked full-time at the bank where her brother was now president, and continued her activities at the local level.

And because all of the above hasn’t quite captured Modjeska’s feisty, fearless personality, below are some quotes pulled from Modjeska Monteith Simkins A South Carolina Revolutionary by Becci Robbins. A full PDF of the pamphlet

There is no more debased and groveling a slave than one who sees what is wrong but who fears man so much more than he does God that he cannot gather the strength to speak out loudly against that wrong.

I don’t want to see anybody suffer. You know we are all a part of humanity, and when one of us loses, we all lose. When one human being dies, each of us dies a little bit, too.

Until the silent majority takes over from the vocal minority, nothing in this state will change.

I don’t know how it is in white churches; I know how it is in the black churches. They get the women to do the hard work, but when officers are elected, it is very seldom that they put a woman in position. That’s also true in almost any organization.

America’s slumbering millions — as much brainwashed and hoodwinked on the violation of their liberties as any people — must be awakened to the onslaught on the bedrock of their liberties.

Good morning, Pond Dwellers. Thanks, DoReMi, for another great herstory lesson. You make me want to go back to school and take some women and black history classes.

As true today as the day it was first spoken.

The kids flew away to New Orleans for 4 days and 3 nights of celebration for their 5th wedding anniversary. It’s just me and Boo. I figure I’ll buy her a new bag of treats today and she won’t miss them at all. I’m pretty sure I will be just fine, so no treats for me. I will, however, get a fresh cup of coffee.

Oh, I don’t know…I think you should definitely get yourself some treats. Just in case… ;D

Treats for me, too, then. Better safe than sorry.

{{{DoReMI}}} – wonderful history/herstory I didn’t know, as usual. About a woman who did the work but didn’t get credit, as usual. She was ever-lovin’ right on a whole slew of things but the “silent majority” one and the “women do the work” one are whang in the gold bullseyes! Then and now.

Sorry to be so late to the party as it were but we’ve got a front moving in (as my joints are testifying – loudly) and I wanted to both get a walk in and get some outside work done before it did/does. Not quite here yet – the wind is in the process of shifting from south to north and at the moment is SWS – but the barometric pressure is shifting ahead of the wind. So. I’ve gotten my walk and some wood in and now can have lunch, relax, and read. :) Thank you again and moar {{{HUGS}}}

Afternoon pond dwellers…Thanks Sher…Another wonderful diary…Always nice to read about people that aren’t in the national consciousness but were remarkable in their contributions.