The true predecessor of Janus is Lochner v. New York, “the notorious 1905 decision that turbocharged the court’s pro-business interventions into health, safety, and economic regulation.”https://t.co/Q4hUsv5OwS

— MissAnthrope (@LyssAnthrope) July 2, 2018

Like most non-lawyers, I struggle to understand the nuances of Supreme Court decisions, and I rely heavily on SCOTUSBlog (found here) to explain decisions in terms that I can understand. When the Janus v. AFSCME decision came down, followed by Justice Kennedy’s retirement announcement, I heard a lot of people talking about a return to the Lochner era. I had a vague recollection of the decision, but that mostly consisted of Lochner = bad. Today’s post is my IANAL attempt to provide an overview of the 1905 Lochner decision.

Context: Herbert Spencer and prevailing attitudes

Bernard Schwartz, a legal scholar and historian once wrote, “The law is both a mirror and a motor.” To view the “mirror”, it’s helpful to be aware of influential ideas that were prevalent during the height of U.S. industrialization and influenced the Fuller Court, which ultimately decided Lochner v. New York. One of the leading thinkers of the late 19th century was Herbert Spencer, a British philosopher who practiced “scientism”, the attempt to apply scientific principles and practices to the social sciences and humanities. It was Spencer, not Darwin, who first introduced the phrase “survival of the fittest” into the lexicon, and when applied to a societal, rather than biological, concept, social Darwinism was born; he developed a philosophy which centered the individual:

That Spencer first derived his general evolutionary scheme from reflection on human society is seen in Social Statics, in which social evolution is held to be a process of increasing “individuation.” He saw human societies as evolving by means of increasing division of labour from undifferentiated hordes into complex civilizations. Herbert Spencer

In his view, society was akin to an organism which existed to benefit its members; members did not exist to benefit society. It was a delicate balance which could be disrupted with the interference of outside forces, including government.

Spencer did not relish making harsh pronouncements, and he was further troubled by the surprising outcome of his rules. Taxing for town sewers was condemned by Spencer as being contrary to the principle that when the government attempted to do something for the citizen which he can do himself, then the government was guilty of depriving the citizen of freedom, and that, Spencer said, was government aggression. (Herbert Spencer and scientism, Sharlan, Harold Issadore, Annals of Science, 33, (September 1, 1976), p. 462)

More of Spencer’s books sold in the United States than they did in England, probably aided by the fact that rugged individualism was already part of the American mythos. It is not known if the justices of the Fuller Court had read Spencer (although there is compelling evidence that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes had), but it is safe to assume that his theories had become enough a part of the popular culture of the time to have some influence. The Fuller Court was to take the mirror, however, and become its motor.

The basics of the case

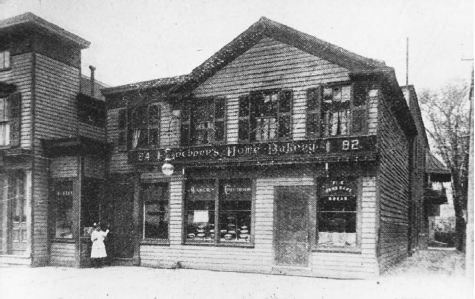

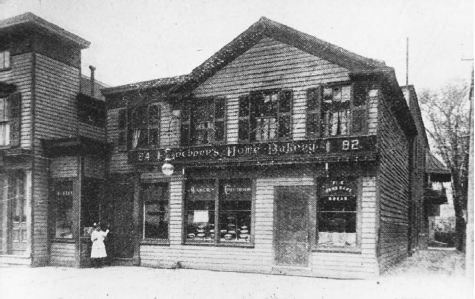

The state of New York enacted a statute known as the Bakeshop Act [ed. in 1895], which forbid bakers to work more than 60 hours a week or 10 hours a day. Lochner was accused of permitting an employee to work more than 60 hours in one week. The first charge resulted in a fine of $25, and a second charge a few years later resulted in a fine of $50. While Lochner did not challenge his first conviction, he appealed the second, but was denied in state court. Before the Supreme Court, he argued that the Fourteenth Amendment should have been interpreted to contain the freedom to contract among the rights encompassed by substantive due process. Lochner v. New York

It is worth noting that although Section 1 of the act talks about the limitations on hours worked, there are four additional sections which address newly-required, minimum sanitary regulations. During this period in New York, many bakeries were housed in the basements of tenements with dirt floors which could easily support the weight of the ovens.

These spaces, however, had never been intended for commercial use. Whatever sanitation facilities the tenements had—sinks, baths, and toilets—drained down to sewer pipes in the cellar, which leaked and smelled foul, especially in the heat generated by the baking ovens. Ceilings in cellar bakeries were as low as five and a half feet (about one and a half metres) above the floor, a height that would force most workers to stoop. There were few windows, so even in the daytime little light came in. In the summer workers suffered intense heat, and in winter even the heat of the oven could not keep the bakeries warm. The lack of adequate ventilation also meant that flour dust and fumes, natural in any baking, could not escape. Lochner v. New York

The Act addressed these sanitation issues, with rules about plumbing and sanitation, the types of flooring and walls allowed, the proper storage of flour, and a requirement for bathrooms to be separated from the bakeroom. (The text of the act, which is very short, can be found here. Choose “See other formats” for a more readable version.)

Lochner v. New York: The Argument

The question that eventually made its way before SCOTUS was, “Did the Bakeshop Act violate the liberty protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment?” Lochner’s argument:

Weismann [Lochner’s attorney] argued on behalf of Lochner that the Bakeshop Act violated the Constitution’s protection of the “liberty of contract,” or an employer’s right to make a contract with his employee free from governmental interference. Weismann’s brief argued that it was wrong that “the treasured freedom of the individual … should be swept away under the guise of the police power of the State,” and that the law was a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. (Police power in this context means the state’s power to issue laws and regulations to protect public health, safety, and welfare.) Lochner v. New York: Fundamental rights and economic liberty

Essentially, Lochner was claiming that the Act interfered with his right to contract labor, as well as the employee’s right to sell his labor. Weismann additionally argued that the “average bakery of the present day is well ventilated, comfortable both summer and winter, and always sweet smelling.” (Lochner v. New York) SCOTUS had made previous rulings that held that the due process clause protected the right to contract (Allgeyer v. Louisiana 1897), as well as upholding the right to regulate working hours (Holden v. Hardy 1898), but with important caveats. In Allgeyer, the right to contract was not viewed as an absolute, and there were instances where the police power of the state could be given precedence. Conversely, Holden held that police power, when used to preserve public health, safety, or morals, was justifiable.

Lochner v. New York: The Decision

ERROR TO THE COUNTY COURT OF ONEIDA COUNTY, STATE OF NEW YORK. In a 5-4 decision, with the majority opinion written by Justice Rufus Peckham, the conviction of Lochner under the Bakeshop Act was reversed. From Peckham’s opinion:

The question whether this act is valid as a labor law, pure and simple, may be dismissed in a few words. There is no reasonable ground for interfering with the liberty of person or the right of free contract by determining the hours of labor in the occupation of a baker. There is no contention that bakers as a class are not equal in intelligence and capacity to men in other trades or manual occupations, or that they are able to assert their rights and care for themselves without the protecting arm of the State, interfering with their independence of judgment and of action. They are in no sense wards of the State. Viewed in the light of a purely labor law, with no reference whatever to the question of health, we think that a law like the one before us involves neither the safety, the morals, nor the welfare of the public, and that the interest of the public is not in the slightest degree affected by such an act. The law must be upheld, if at all, as a law pertaining to the health of the individual engaged in the occupation of a baker. It does not affect any other portion of the public than those who are engaged in that occupation. Clean and wholesome bread does not depend upon whether the baker works but ten hours per day or only sixty hours a week. The limitation of the hours of labor does not come within the police power on that ground. Lochner v. New York

Since Peckham had rejected the argument that a maximum hours law for miners was a legitimate health issue in Holden v. Hardy, it is no surprise that he dismisses the hour limitation as a health issue in Lochner:

We think that there can be no fair doubt that the trade of a baker, in and of itself, is not an unhealthy one to that degree which would authorize the legislature to interfere with the right to labor, and with the right of free contract on the part of the individual, either as employer or employee. In looking through statistics regarding all trades and occupations, it may be true that the trade of a baker does not appear to be as healthy as some other trades, and is also vastly more healthy than still others. To the common understanding, the trade of a baker has never been regarded as an unhealthy one. Lochner v. New York

Peckham further dismisses the regulation as a return to 17th and 18th century paternalistic government:

It seems to us that the real object and purpose were simply to regulate the hours of labor between the master and his employees (all being men sui juris) in a private business, not dangerous in any degree to morals or in any real and substantial degree to the health of the employees. Under such circumstances, the freedom of master and employee to contract with each other in relation to their employment, and in defining the same, cannot be prohibited or interfered with without violating the Federal Constitution. Lochner v. New York

I’m going to stop at this point with the hope I have provided enough information to incite curiosity and encourage discussion. Next week (and maybe one further week), I will cover the Harlan dissent, as well as Justice Holmes’ dissent, which some legal and constitutional experts feel is the most famous of all dissents and has been described (by Judge Richard Posner) as a “rhetorical masterpiece.” I’ll also be exploring the ramifications of Lochner, both then and now; what a “return to the Lochner era” means; and how discussions of Lochner today invariably lead to discussions of Roe and Obergefell.

{{{DoReMI}}} Thank you for your research and work on this. To the Free Market people “free” means “free to do whatever we market owners want to for whatever reason we want to no matter how many people or systems it kills in the process” – the only rein on corporations was the incorporation process and requirements themselves. And over the last 50 years those have been eroded to just about nothing.

The societal goliaths are again encoding into law restrictions on how the davids of the world are allowed to interact with them. Which ultimately (and after a lot of death and hardship) backfires as we finally resort to rocks – and somebody gets lucky. About the best I can say about everything going on right now is that we’ve been there before. No matter how far they push us back, we’ve been there before. But it’s no longer “what is” – now it’s recognized as wrong, we have at least some ideas of what’s right, and the path to right has been cut and walked at least once already. It will be faster to recover this time. {{{HUGS}}}

Thanks, bfitz. I originally envisioned this as a one-and-done post, but the more I read, the more I realized that the 14th Amendment in general and Lochner in particular are going to be a central part of our discourse over the next few years. Reading conservative legal sites has been eye-opening; they’ve been gunning for the various sections of the 14A for years. One of the books I have that was used as a resource was written by a noted legal historian and published in 1993. He started the chapter on Lochner talking about how it had long been considered one of the worst SCOTUS decisions ever, right up there with Plessy. He ended the chapter talking about how, to his astonishment, attempts were being made to rehabilitate Lochner. Now they have their chance.

OMG. Thank you, DoReMI, for researching and writing this post. I had been wondering what Lochner was about, so your essay was most welcome.

It seems to be all going south, doesn’t it? As a proposal slave I was routinely required to work more than 60 hours a week when a proposal was due. I did get paid time-and-a-half for it, but it was as hard on me as it was on everyone else. That’s one of the reasons I took early retirement at age 62. It was just burnout.

But I didn’t have to work in dangerous, insanitary conditions! Sometimes I’m glad I’m old, so I won’t have to see how life has deteriorated for 99 percent of the American people.