For the past two weeks, I’ve been discussing Lochner v. New York, the opinion, and the dissents. This week it’s time to take on the some analysis; both the once-prevalent view that, “Aside from Dred Scott itself, Lochner v. New York is now considered the most discredited decision in Supreme Court history” (A History of the Supreme Court by Bernard Schwartz, Oxford University Press, 1993. p. 190) and more recent efforts to “rehabilitate” Lochner.

The opinion and dissents in Lochner illustrate two differing views on the role of jurisprudence: one that was, to that point, the prevailing view, and one that was to become the prevailing view in the future. Justice Peckham held that the following question must be answered:

…the question to be determined in cases involving challenges to Lochner-like legislation is: “Is this…fair, reasonable and appropriate…or is it an unreasonable, unnecessary and arbitrary interference with the right of the individual?” (A History of the Supreme Court, Bernard Schwartz, Oxford University Press, 1993. p. 197)

In Lochner, Peckham found the latter:

The Peckham opinion indicated that the reasonableness of the challenged stature must be determined as an objective fact by the judge upon his own independent judgment. In holding the Lochner law invalid, the Court in effect substituted its judgment for that of the legislator and decided for itself that the statute was not reasonably related to any of the social ends for which the police power might validly be exercised. (A History of the Supreme Court, Bernard Schwartz, Oxford University Press, 1993. p. 198) (emphasis added)

Justice Holmes had his own test of “reasonableness,” but as an advocate of judicial restraint, his came from a different perspective. He felt a more subjective test should be used by asking, “Could rational legislators have regarded the statute as a reasonable method of reaching the desired result?” As he articulated in a dissent written for a 1923 case Adkins v. Children’s Hospital, “The criterion of constitutionality is not whether we believe the law to be for the public good…We certainly cannot be prepared to deny that a reasonable man reasonably might have that belief.” Additionally, in a 1919 case Hebe Co. v. Shaw, Holmes wrote in his opinion:

If the character or effect of the article as intended to be used “be debatable, the legislature is entitled to its own judgment, and that judgment is not to be superseded by the verdict of a jury,” or, we may add, by the personal opinion of judges, “upon the issue which the legislature has decided.”

More importantly, the Peckham/Holmes disagreement was fundamentally over whether the judiciary should decide cases based on economic theory. For Peckham, Lochner violated the “unfettered operation of the market and the freedom of contract” (Schwartz, p. 199) which were fundamental and foundational principles for his jurisprudence. Holmes, on the other hand, did not believe it was the role of the Supreme Court to “dogmatize on social or economic theories.” (Schwartz, p. 198) This was a role properly left to the legislature. As he stated in his dissent to Baldwin v. Missouri in 1930,

I have not yet adequately expressed the more than anxiety that I feel at the ever increasing scope given to the Fourteenth Amendment in cutting down what I believe to be the constitutional rights of the states. As the decisions now stand, I see hardly any limit but the sky to the invalidating of those rights if they happen to strike a majority of this Court as for any reason undesirable. I cannot believe that the Amendment was intended to give us carte blanche to embody our economic or moral beliefs in its prohibitions. (emphasis added)

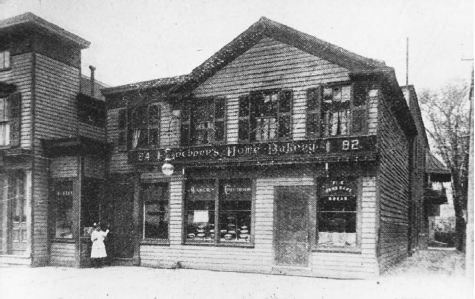

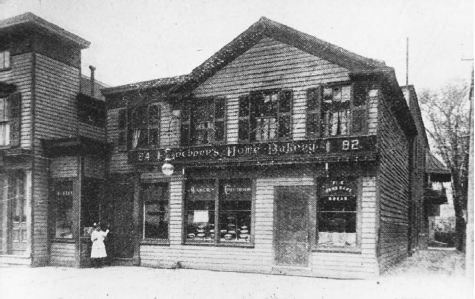

When the Lochner decision was released, it was considered a relatively minor decision and not particularly controversial. The majority opinion reflected the conventional wisdom of the time, and the right to contract which Peckham so staunchly upheld was viewed in contrast to the perils of indentured servitude and apprenticeships, which were often abused (not, however, slavery, despite the 14th Amendment being a Reconstruction-era amendment). The Bakeshop Act was held to have come about due to the agitation and lobbying of unions (with some validity) and was further viewed as being detrimental to small, independent bakeries (also with some validity). In an April 28, 1905 editorial, the New York Times wrote:

The tendency of State Legislatures, under the pressure of labor leaders and professional agitators, to enact laws which interfere with “the ordinary trades and occupations of the people” is sharply checked by this decision….It is believed that the views of the court will have a strong influence with Congress to reject the Gompers Eight-Hour Bill, which, while differing in many essential particulars from the New York law, still undertakes to regulate the hours of labor in arbitrary abrogation of contract stipulations.

(The New York Times may have been right; the first federal 8-hour day act applied only to railroad workers; the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1937 expanded this so that about 20% of working Americans were covered by Federal law. However, most industries that [already] had an 8-hour work day did so because of union contract negotiations.)

On the other hand, in many ways Lochner was the apogee of the Peckham approach. In a 1943 Circuit Court decision , the Peckham approach was described as a time when:

when legislatures were being admonished that, except in unusual circumstances, it was unconstitutional to intrude upon the inalienable right of employees to make contracts containing terms unfavorable to themselves, in bargains with their employers, the courts would not, of their own motion, venture thus to intrude. An ordinary worker was told, if he sought to avoid harsh contracts made with his employer (when fraud or the like was absent), that he had acted with his eyes open, had only himself to blame, must stand on his own feet, must take the consequences of his own folly. Hume v. Moore-McCormack

Some of the swing away from the laissez faire approach embodied in Lochner was due to the rise of industrialization, the strengthening of unions, and the recognition that dangerous work conditions did indeed pose a real need for police powers in the area of worker safety. Additionally, Teddy Roosevelt, somewhat cynically and with political intent, railed against conservative courts as enemies to his populist progressivism.

Theodore Roosevelt was among those strongly opposed to the position assumed by the Lochner Court; in correspondence with Justice Day, he commented: If the spirit which lies behind [Lochner v. New York] obtained in all the actions of the Federal and State Courts, we should not only have a revolution, but it would be absolutely necessary to have a revolution, because the condition of the worker would become intolerable. The Supreme Court and Constitutional Change: Lochner v. New York Revisited

The Progressive Era and later years found less reason to fight for the freedom of contract and more reason to consider that the State had an interest beyond those of the individual.

There was to be a swing, later in the 20th century, away from this excessive emphasis on liberty of contract;[12] see e.g. West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, 300 U.S. 379, 391-394, 57 S.Ct. 578, 581, 81 L.Ed. 703, 108 A.L.R. 1330, 1937, where the court (per Chief Justice Hughes), summarizing previous decisions, said, “The Constitution does not speak of freedom of contract. * * * [The] power under the Constitution to restrict freedom of contract has had many illustrations. That it may be exercised in the public interest with respect to contracts between employer and employee is undeniable”; the court refused to accept it as a dogma “that adult employees” must invariably “be deemed competent to make their own contracts”. Hume v. Moore-McCormack Lines

It is worth noting that West Coast Hotel v. Parrish used as an example above is the SCOTUS decision credited with ending the Lochner era. Although the decision explicitly overturned Adkins v. Children’s Hospital rather than Lochner, it marked a shift away from the laissez faire understanding to a more hands-on view that was largely to continue until Rehnquist became chief justice in 1986.

Until recently, Lochner was often repudiated in the same breath as the Dred Scott decision. However, in 1985, an article appeared in the San Diego Law Review entitled, “Rehabilitating Lochner,” a book entitled, Rehabilitating Lochner was released by David Bernstein in 2011, and the efforts have continued unabated ever since. A significant number of the arguments are based on the premise, “Right result, wrong rationale.” These reviews contend that the Bakeshop Act was flawed from the start, because it reflected the State’s need for industrial bakeries (large output) without admitting as such, and as a result, unfairly hampered the small bakery (and to some, not coincidentally, Jewish bakers). Others, like economist (Chicago School) and legal giant, retired-Judge Richard Posner (who considers the Holmes’ dissent brilliant) thread the needle (and here, received pushback):

Judge Posner writes that he “was the first to suggest that the discredited ‘liberty of contract’ doctrine could be given a solid economic foundation and as good a jurisprudential basis as the Supreme Court’s aggressive modern decisions protecting civil liberties.” Nevertheless, Posner denies advocating the Lochner approach, declaring, “I have never believed, however, that such a restoration of the ‘Lochner era’…would be, on balance, sound constitutional law. The denial is disingenuous. The Posner approach lends direct support to the effort to take our public law back to Lochner. With efficiency and wealth maximization as its end and the market as the instrument through which it is achieved, Posnerian jurisprudence leads to what Posner himself terms the constitutionalization of laissez faire. (Schwartz, p. 201)

The overt attempts to rehabilitate Lochner have become obvious with the Roberts Court. As outlined in a June 2018 Slate article, we are returning to the days when business is favored over labor:

Both Lochner and Adair rested on the premise that the Constitution protects an individual’s right to sell his labor at any cost. This doctrine trammeled minimum wage and maximum hour rules, as well as laws safeguarding workers’ right to unionize. Janus restores this premise in a slightly altered form, replacing “liberty of contract” with “associational freedoms.” The upshot is the same: Laws designed to benefit labor’s ability to act collectively are inherently suspect. (A New Lochner Era)

In addition, the Court is substituting its judgment for those of legislators in areas beyond labor:

The same conservative majority that hamstrung unions and class actions in Janus and Epic Systems also directed its activism toward women seeking abortions. Like every other state, California has myriad “crisis pregnancy centers,” which masquerade as women’s health clinics but actually impose religious, anti-abortion ideology on their unwitting “patients.” To safeguard women against fraud and misinformation, California passed the FACT Act, which compels these clinics to post a sign providing information about low-cost reproductive health services (including abortion) provided by the state. It also requires CPCs that lack a medical license to disclose this lack of license in signage and advertising.

Wielding the First Amendment as a sword, the court blocked the FACT Act as a violation of CPCs’ free speech. But Justice Clarence Thomas’s opinion for the 5–4 court in NIFLA v. Becerra didn’t stop there. It also questioned the validity of countless regulations by declaring that the government has little leeway to regulate “professional speech,” even in the practice of medicine. Thomas added one exception: States can force doctors to provide anti-abortion propaganda to their patients. (A New Lochner Era)

At the core of these decisions is a return to a diminishment of public interest and an elevation of the unrestrained “market.” We have yet to see if tightly-written State and Federal laws can overcome a new Lochner era, but we won’t stand a chance if we don’t elect Democrats to legislatures.

Next week: Good news: I’m going to step away from the Supreme Court for awhile! Bad news: I’m currently reading a book about the history of lynching in our country…

Good morning DoReMI, and thanks. I wonder who the Justice Holmes of our time will be?

Holmes was an interesting and complex guy. He was very principled, disciplined, and consistent when it came to judicial restraint. There was a case before SCOTUS in 1923 or so (my notes are home, and I’m at work, so bear with me…) about a Nebraska law which forbade the teaching of foreign languages in schools for grades 1-8. There were a lot of laws like this on the books in response to the anti-German propaganda during WWI, and there were also a lot of private Lutheran schools who taught German, because so many of their students were children of German immigrants. Anyway, to make a long story short, the Supremes struck down the law in Meyers v. Nebraska; Holmes wrote a dissent, basically arguing “let legislatures legislate.” But he wasn’t an absolutist; he did feel there were times when legislatures went too far and tried to abrogate the legitimate police powers of the State and thus were in violation of the Constitution. It’s interesting to consider how he would feel about the state laws about abortion clinics, which are couched in terms of “regulating for the safety of the patient” when really they exist to make abortion difficult, if not impossible. I don’t know what his answer would be.

I also haven’t read enough of the opinions from current justices to answer your question. Oddly, though, my first thought was Scalia. There’s no question he was brilliant, and in his own way, he was principled. Unfortunately, his principles ended up getting twisted in knots, because originalism will do that to you; there are enough built-in contradictions to that philosophy/approach, that it’s next-to-impossible to stay both principled and consistent. Scalia ended up Lochnerizing himself, because of those internal inconsistencies in originalism. It’s a shame that his example is exalted on the Right, rather than analyzed. Because it’s not, we end up with a Gorsuch and potentially a Kavanaugh, who both ride the originalism train.

{{{DoReMI}}} – the self-serving votes and decisions of those Jurists bought and paid for by corporations have ever been a problem in America. And just about everywhere else. We are the United States because no single state/colony was strong enough to fight off Britain by itself. No single employee or prospective employee is strong enough to “contract” with employers for safe working conditions (which includes maximum hours) or anything approaching a living wage. Stronger Together isn’t just a slogan – it’s the way ordinary people survive. But there are enough ordinary people that the corporations really don’t care about us surviving. “Dime a dozen” is the way they think of us and our labor. If one dies or quits, there’re always more begging for jobs. Just one more application of Genocidal Old Party’s Deplorable govt – of whatever era.

Can’t say I’m looking forward to your next topic. I know enough to have nightmares already. But it’s work that must be done so thank you for doing it. moar {{{HUGS}}}

I’m actually probably not going to do lynching, except indirectly. There are some tangential issues related to the topic worth exploring, but I see no need, nor do I have the desire, to write a post which would qualify as graphic shock-porn. So you can breathe easier…and if I think of another topic, I’m likely to go that way, because I need a break too!

Thank you. I’m not trying to ignore or erase the history. It was – still is – gawdawful bad. I have read about it, know about it – and even songs like “Suppertime” that just sort of refer to it make me nauseous. Other than working for the candidates I support, voting for people determined to “make things better” I don’t know where to go from here. But I can’t do whatever little bit available for me to do if I’m too sick to do it. I know that’s chickenshit – black folks lived with this, generations of it, centuries of it. I don’t know how they survived but they did. I’m not that strong. But what little strength I have, well, I am trying to use to help “make things better”.