Throughout the course of Labor Day, we see reminders of what unions have accomplished for all of us; tweets like this are typical:

Happy #LaborDay! We’re grateful for all that organized labor has done for workers, and we’ll support them as they strive for equitable wages, dependable pensions, and workers’ rights in the future.#ALDems #alpolitics #NewEraForAlabama pic.twitter.com/Zxt7FG682a

— Tuscaloosa Dems (@TuscaloosaDems) September 3, 2018

Sadly, this anodyne and misleading tweet from the GOP is also typical:

Today we celebrate and honor the force that drives our country forward: the American worker. #LaborDay pic.twitter.com/B91vl5OJZo

— GOP (@GOP) September 3, 2018

What gets lost amidst the parades and barbecues, speeches and parties, politicians and public is the often costly path that was necessary to make the gains we now so-often take for granted. Today, I’m going to share one story: the story of the Battle of the Overpass.

1937 was the year GM and Chrysler autoworkers won recognition of the UAW as their representative (after massive sit-down strikes); Ford was next, but, because of Ford Motor Company’s paternalistic history, would be a tougher nut to crack.

To hear many old-timers tell it, they didn’t work at Ford; they worked for Ford’s. Henry Ford was an opinionated autocrat (and a racist and an anti-Semite, but this post isn’t about that) who often expressed his views in a paternalistic way. While the history books laud him for raising the minimum daily wage to $5 in 1914 (from $2.34; in 2018 dollars that $5 is the equivalent of $123.26), what they rarely mention is the rules and conditions that came with the pay raise.

The $5 a day rate wasn’t just free money, that every worker got. Instead, you had to work at the company for at least six months, and you also had to buy in to a new set of rules. The extra pay came at a price.

As Richard Snow writes in his book I Invented the Modern Age: The Rise of Henry Ford, a few basic stipulations were laid from day one: To qualify for his doubled salary, the worker had to be thrifty and continent. He had to keep his home neat and his children healthy, and, if he were below the age of twenty-two, to be married. When Henry Ford’s Benevolent Secret Police Ruled His Workers

To ensure that the rules were followed, Ford created the Sociological Department, which acted as Ford’s enforcers. Home visits were conducted, and the “investigators” could inspect the cleanliness of your home; check that your children were in school; ask about your drinking habits; and even grant or deny the company’s permission to buy a car (which included the further requirement that one be male, married, and have children). The paternalism was intertwined with Henry Ford’s definition of patriotism, and workers were required to learn English. Although this requirement did have a safety/communication element for those working the line, and was unprecedented at the time, the graduation ceremony from the Ford English School shows that safety was not the sole concern:

The culmination of the Ford English School program was the graduation ceremony where students were transformed into Americans. During the ceremony speakers gave rousing patriotic speeches and factory bands played marches and patriotic songs. The highlight of the event would be the transformation of immigrants into Americans. Students dressed in costumes reminiscent of their native homes stepped into a massive stage-prop cauldron that had a banner across the front identifying it as the AMERICAN MELTING POT. Seconds later, after a quick change out of sight of the audience, students emerged wearing “American” suits and hats, waving American flags, having undergone a spiritual smelting process where the impurities of foreignness were burnt off as slag to be tossed away leaving a new 100% American. Ford Motor Company Sociological Department & English School

Those who did not follow the rules for being a good worker for Ford would pay a heavy price:

But if you didn’t live up to the standards of Henry Ford and his Investigators, you were doomed. If you didn’t toe the line, you were initially blacklisted, and your prospects for promotion and advancement would vanish. Then you’d see your pay cut back to $2.34. If you still didn’t get the message of “speak English, get married, and be a good little American,” after six months, you’d be fired. When Henry Ford’s Benevolent Secret Police Ruled His Workers

From Paternalism to Corporate Terrorism

Although by 1922, Ford himself was moving away from and discontinuing much of the work of the Sociological Department, the paternalistic management approach did not end. Much of the control of the company was handled by Harry Bennett, a former sailor and boxer, who became Ford’s right-hand man and enforcer. Initially hired after Ford heard a story about a street brawl involving Bennett, he was intended to be a bodyguard for Ford and his family in an era when fear of kidnapping was rife. A position was created for him in the Highland Park Ford Plant art department, but within five years, Bennett rose to become head of the Ford Service Department. The Service Department was internal security at Ford; under the guidance of Bennett, a network of thugs, spies, and informers, often hired from the ranks of petty criminals and organized crime in Detroit, grew strong with responsibility for monitoring Ford employees, intimidating union organizers, delivering punishment as they saw fit, co-opting local police, and even ensuring that stories of Henry Ford’s affairs were suppressed. Ensconced in a basement office of the River Rouge Ford Plant, Bennett ruled over the company’s largest plant with the full support of Henry Ford and the charge to ensure that Henry Ford’s will was enforced. These were not nice people.

Despite that knowledge, many workers hoped that Ford’s paternalistic impulses could be leveraged for the good. In 1932, when many workers had been or were facing layoffs of six months or more due to the Great Depression, a Ford Hunger March was organized.

The organizers of the 1932 Ford Hunger March, by many reports, didn’t intend for their demonstration to erupt in violence. Instead, unemployed auto workers – many of them laid off from Ford’s massive River Rouge plant at a time when unemployment insurance and welfare were nonexistent or scarce – wanted to communicate their plight to Henry Ford himself, figuring that in exchange for making millions off their labor he should take care of his workers. Looking back on ‘The Battle of the Overpass’ — 78 years later

Bennett was unmoved by the plight of the laid-off workers and saw their organization as a threat to Ford Motor Company and a possible precursor to unionization.

This goon squad could be deadly. On a brutally cold winter day in 1932, a couple years into the Great Depression, unemployed Ford workers took part in the “Ford Hunger March,” a procession of 3,000 men from the Detroit city line toward Ford’s Rouge Complex. Bennett’s men were ready with a complement of Dearborn police, armed with fire hoses, tear gas, and machine guns. They opened fire on the protesters. Bennett himself was driven out in a car where he emptied two pistols into the crowd before he was pelted with rocks and knocked unconscious. When the smoke cleared, four protesters were dead, and dozens more shot. Eventually a fifth protester died. Looking back on ‘The Battle of the Overpass’ — 78 years later

The Battle of the Overpass

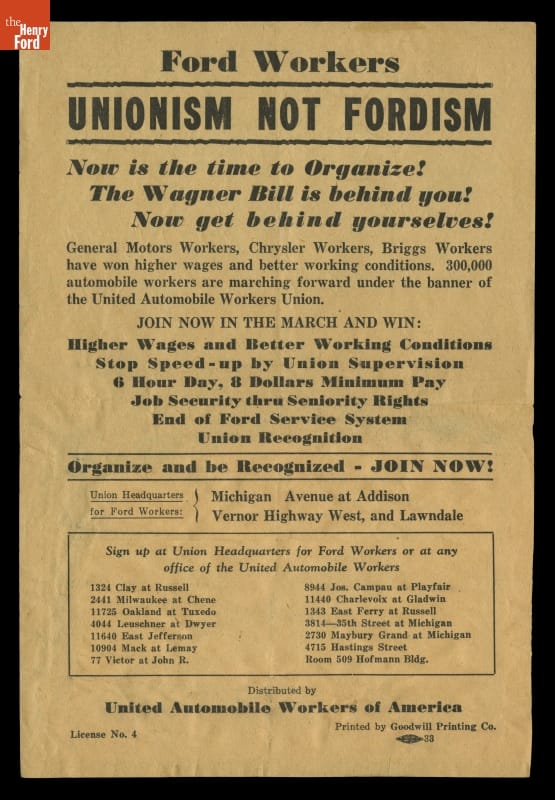

In 1937, when UAW organizers turned to Ford, the actions at the Ford Hunger March combined with the daily abuses in the Rouge plant were well remembered. But the fledgling UAW (formed in 1935) had opted for a bold strategy of organizing; rather than unionizing small local after small local, they targeted the largest plants (Flint for GM and all nine of Chrysler’s Detroit plants concurrently), and with roughly 9000-13,000 workers, the Rouge plant was the natural target. Armed with rights afforded under the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, which included the right to distribute informational brochures at factory gates, the UAW made plans to distribute flyers.

The UAW action did not happen overnight and involved extensive planning.

The workers in the Rouge plant held secret meetings to discuss joining the UAW and to plan for the upcoming protest at Gate 4 of the Miller Road Overpass. Reuther meanwhile obtained his license to demonstrate from the city hall in Dearborn, as corrupt a city if ever there was, opened two union halls, and made a couple of forays to the Overpass to scout out and plan the logistics. Knowing that the union organizers might be sitting ducks for Ford’s Gestapo, he extended a welcome for others to join the UAW in the march, including clergymen, reporters and journalists, along with members of the Senate Committee on Civil Liberties. One hundred women, members of the Women’s Auxiliary of the local, were to help distribute the leaflets. Battle of the overpass: Henry Ford, the UAW, and the power of the press

Initially, the distribution of flyers went fairly well. Although two dozen carloads of Ford Service Department representatives arrived shortly after the action started, beyond some pushing and shoving of reporters, the action continued unabated, despite a warning to the union organizers to move on. It was calm enough that a Detroit News photojournalist suggested a posed photo of UAW representatives with the Rouge plant in the background.

After many workers took the flyers that the roughly 40 organizers had been passing out all day long, UAW organizers Walter Reuther, Richard Frankensteen, and two more gathered on the pedestrian overpass over Miller Road at gate 4 of the plant for photos by Detroit News photographer James R. “Scotty” Kilpatrick. The Ford logo was behind them, which is why they chose that spot. Nearly 80 years ago, the Battle of the Overpass was a national PR disaster for Ford Motor Company

Almost immediately, the Ford Service Department stepped in, and violence erupted.

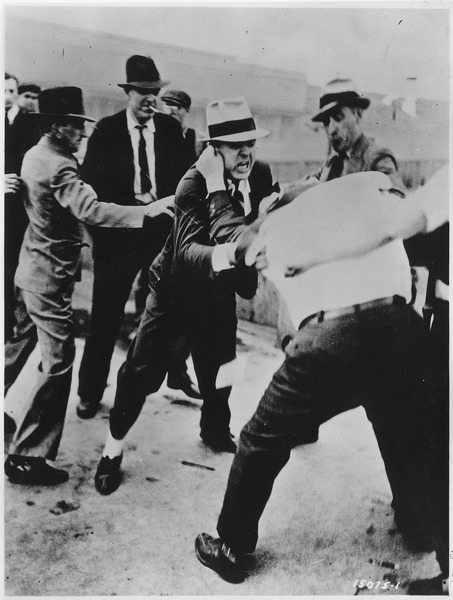

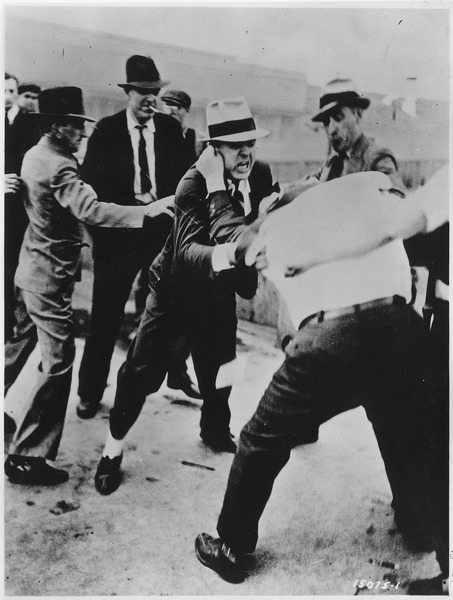

![National Archives and Records Administration [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.motleymoose.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/lossy-page1-767px-Labor-Strike-Ford_Motor_Company-Walter_Reuther_fifth_from_the_left-Richard_Frankensteen_sixth_from_the_left_-_NARA_-_195593.tif.jpg)

In an interview in the Detroit News after the beatings, Reuther explained what happened. “Seven times they raised me off the concrete and slammed me down on it. They pinned my arms…and I was punched and kicked and dragged by my feet to the stairway, thrown down the first flight of steps, picked up, slammed down on the platform and kicked down the second flight. On the ground they beat and kicked me some more.” Many of the other organizers were also beaten severely, and one got a broken back out of the ordeal. Battle of the overpass: Henry Ford, the UAW, and the power of the press

The press and photojournalists were also pursued. Kilpatrick, the Detroit News photographer was only able to preserve his photos by hiding the plates under his backseat. When the Service Department thugs reached his car, he was able to hand them unused plates which they smashed on the ground. He returned to his Detroit office in time for his photos to be published on the front page and eventually in newspapers across the country. As severe as the injuries were to the UAW reps, more blood had actually been shed during the Flint GM sitdown strike, but the photos carried a message which mere words had been unable to convey.

In an interview in Time magazine, Harry Bennett tried to cast the blame on union organizers and even went so far as to deny that any Ford Service men or plant police were involved in the violence. The pictures told a different story, and sympathy for the union organizers grew. Additionally, lawyers for Henry Ford and Harry Bennett were called before the National Labor Relations Board to answer charges related to unfair labor practices.

The outcome of the Battle of the Overpass was the negative attention it brought on Henry Ford and the way he treated his workers. Called before the National Labor Relations Board, Ford had to answer charges involving dozens of unfair labor practices in his violation of the Wagner Act. Ironically, the members of the press gave the most damning evidence at the hearing. Ford lawyers tried to undermine the negative effects of their words by asking questions like, “So, you’re a communist?” when reporters gave their credentials as a members of the Newspaper Guild.

Ford workers were questioned about their working conditions and Bennett’s security force. A Time Magazine report stated, “Witness after witness told how he had been suddenly taken from an assembly line by two service men, marched off for his pay and escorted to the gate, with no explanation except his own—that he had just joined the UAW.” One worker testified that he had a blank union application on him, and it fell from his shirt to the floor where it was picked up by another worker. Five days later he was fired; his foreman just said, “I guess you don’t want to work here.” This Day in Resistance History: The Battle of the Overpass

It took until 1941 before Ford and the UAW reached a collective bargaining agreement. The Battle of the Overpass, although not the most violent of anti-labor battles, was instrumental in breaking Fordism and replacing it with unionism. As we reflect on past and future Labor Days, it’s a story worth remembering.

Bonus videos: late 1930s PR short from Ford Motor Company

{{{DoReMI}}} Power corrupts… despotism hidden under paternalism. WASP supremacy and its “white man’s burden” crap. They didn’t/aren’t going to give it up willingly. And we white folks always go through the same process. Seeing that it’s wrong, electing people who “change policy and reallocate resources”, make some hard-won progress. Then think it’s a done deal, go back to ignoring politics, and “not notice” as the progress is eroded. We never make as much progress as we think we did because we never pay attention to where POC are in the mix. We start the process way too late, long after the WASP supremacists are back in power, because we don’t listen to POC when they tell us the gains weren’t made across the board and are eroding fast everywhere. But there’s that Dream out there. Maybe this time we’ll push back the Evil Ones far enough to get everybody closer to it.

Thank you for bringing together the pieces I already knew and completing the picture with pieces I didn’t. ????????????