I’ve written of conservation efforts to preserve our local PNW waters and the salmonids that spawn and live in these streams. In these posts I have periodically mentioned the Nooksack but I have not featured this marvelous River as it deserves.

The Nooksack River is neither a large nor a long river by most standards as it runs only 75 miles from its origin in the glaciers of the North Cascade Mountains to its delta and mouth where it empties into Bellingham Bay to become part of the Salish Sea.

However, its relatively small size does not diminish its importance to the Pacific Northwest and its marine environment. The Nooksack is one of the few streams in the PNW that supports all five native pacific salmon species as well other salmonids such as steelhead and the rare Bull trout.

This river’s name recognizes the Salishan speaking tribes of Southwest British Columbia and Northwest Washington/Puget Sound. The name “Nooksack,” applied to the tribe, comes from a Salish place name encompassing the area including the mountains, valleys, the watersheds and shores of this river and its surrounding territory. “Nooksack” translates to “always bracken fern roots,” a food staple for this and many Native American populations. However they seem not have had a specific name for the river as a whole, other than “river, ”although they did have place names for various fishing, digging and hunting sites along the river and throughout its tributaries.

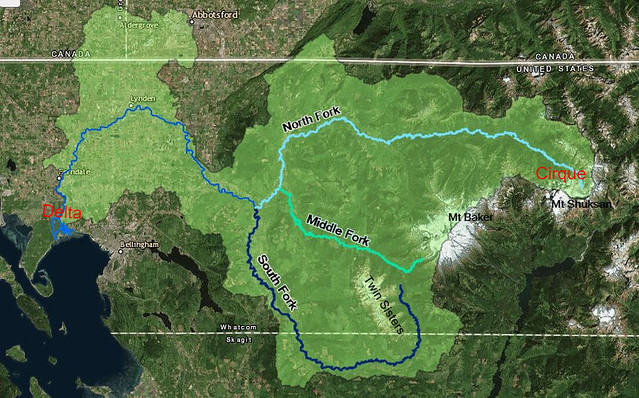

The river comprises three forks and numerous smaller tributary creeks that converge to form the Nooksack river before it flows into Bellingham Bay. Each of the forks originates within the Mount Baker – Snoqualmie National Forest and the Mount Baker Wilderness Area. I’ll describe the source area for each fork and its confluence with the main stream. These forks drain the forest basin of 786 sq. mi. of this portion of the Cascade Range including the glaciers of Mt. Shuksan, Mt. Baker and the Twin Sisters Range and reaches in part across the border into Canada.

Three forks and the main stream of the Nooksack River. North fork begins at Nooksack Cirque at far right and meets Bellingham Bay at the river delta at the far left. Light green covers the river drainage, some of which reaches into British Columbia, Canada.

The North Fork

The North Fork of the Nooksack originates on the North Side of Mt. Shuksan (Salish for ‘Steep and Rugged”) where its glaciers drain into the Nooksack Cirque and, along with numerous creeks become the headwaters of the river.

Mt. Shuksan from Picture Lake with White Salmon Glacier in center.

This fork is considered part of the main stream as it connects with various feeder streams along the way and then with the Middle Fork and the South Fork to form the final version of the river.

The North Fork is probably the most scenic fork as it originates from the Glaciers of Mt. Shuksan and Mt. Baker mostly from the North side. The River then runs through old growth Forest, steep canyons and Waterfalls and eventually wends through lowland farm country to the Lummi Indian Reservation which hosts its delta and its entry into Bellingham Bay.

Only 12 miles from its origin the North Fork comes to the 88 foot high Nooksack Falls which is a scenic and popular photo site. Sadly, his beautiful falls has a deadly history as at least 11 people have fallen off the cliff into the plunge pool, lured by trying to get a better view. It is now quite heavily fenced.

With the spring snowmelt runoff these three falls becomes one big cataract. the pool behind

the falls shows a deep blue-gray of the glacial melt

Moving west, the North fork careens through some sheer walled canyons filled with boulders and downed trees that builds into white water rapids. A wonderful trail follows along the river at Horseshoe Bend and then rises along the canyon wall above the river into some lush forest environs.

North Fork rapids looking down into the canyon at Horseshoe Bend.

Mossy trees bent above the river’s canyon

Devil’s Club (Oplopanax horridus) with berries along the Horseshoe Bend trail. This plant was/is

widely used for many purposes, especially for its medicinal properties by indigenous populations.

The River with boulders and logs washed down with Spring floods, looking North

The North Fork and its surrounding watershed areas is very popular for recreation of many kinds including camping – there are three National Forest campgrounds along this segment of the river as well as several private vacation communities. Other recreational activities available along this fork include: mountain climbing, hiking, fishing, white water kayaking (Class III & IV), river rafting, picnicking and in the winter, skiing and eagle watching, not to mention photographing all of the preceding activities.

A white water rafting tour prepares for a bouncy and wet ride down the North Fork in August

Some of the rapids at Horseshoe Bend. You can see the river plunging downhill.

As the river comes out of the higher mountains, canyons and forest, it broadens and slows a bit forming side streams with gravel and rock bars and becomes quite braided. At Spring high water these bars are covered and the river boils, tumbling along boulders and downed trees.

North Fork, Wildcat Reach showing the river’s bars and braids.

As I noted above, this river is a prime spawning stream for all species of Pacific Salmon. After the eggs hatch, the fry hang around in quiet pools growing and maturing for a year or so before beginning their journey down stream to estuaries where they adapt to the salt water environment.

Salmon fry growing in the cool side waters of the North Fork where they feed and grow in preparation

for their journey down stream and ultimately into the vast reaches of the North pacific.

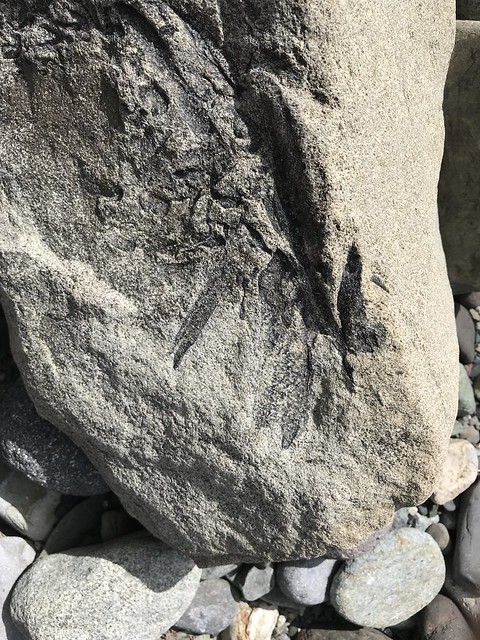

Shale, sandstone and various igneous and metamorphic rocks litter the river bars. As this area is directly below Slide Mountain which is part of the Chuckanut Formation, a 54 million year old sedimentary rock formation from the Eocene epoch, it yields numerous fossils.

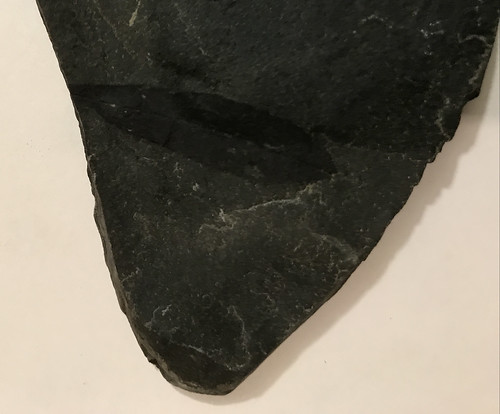

As we poked along the bars I began breaking some of the shale stones to check their insides and sure enough before long my sons and granddaughter were exposing leaf fossils that had hidden inside for over 50 million years.

Leaf Fossil found inside a shale rock on the river bed

Leaf Fossils, similar to one above etched into Chuckanut sandstone on the same gravel bar along

Wildcat Reach of the North Fork. This will be underwater with Spring flooding.

Middle Fork

Mt. Baker viewed from the West. Meltwater from the glaciers on this side form the Middle Fork

The Middle fork originates from the glaciers such as Coleman and Thunder, on the western slopes of Mt. Baker (Komo Kulshan and variants thereof in the Salish language). The connecting creeks gathering the runoff from the glaciers initially run west through some difficult- to-access old growth Douglas Fir and Western Red Cedar. As the creeks converge to form the Middle Fork, they turn north and connect with the North Fork.

Rapids on the Middle Fork at quite low water in August with Spirea douglasii along the bank

The Middle Fork enters the North Fork from the left as they proceed west to soon meet the South Fork

The confluence of these two forks is a favorite feeding spot for bald eagles during the winter where recently spawned salmon carcusses are abundant. This spawning site is less than a mile downstream from North Fork Eagle Preserve and it is another very popular eagle viewing spot for birders during December and January.

Salmon spawning, soon to deposit eggs and then become eagle lunch

A recently spawned salmon goes down the eagle hatch near the confluences of North and Middle Forks

This fork falls rapidly from the big mountain and moves fast before meeting the North Fork. It has some class V white water rapids for competitive kayakers. This fast moving tumbling part of the river was referred to by Native Nooksacks as “Always murky water,” as it was always stirred up and fast running glacial melt.

The South Fork

Twin Sisters Range, immediately West of Mt. Baker — source of the South Fork

The South Fork originates between Mt. Baker and two peaks immediately to its West — The Twin Sisters. One of the South Fork’s tributary streams, Skookum Creek, provides some magnificent viewing and is well worth watching this drone video.

This Fork is the least turbulent of the three and after coming around the south end of the Sisters, it meanders northerly through the Acme valley farm land where we can find several dairies including a Yak farm.

Yaks grazing in farm country along the South Fork.

This part of the River seems downright lethargic compared with the rough and tumble of its upstream counterparts. Instead of white water rafting or kayaking, the South Fork is known for its recreational inner tubing. This Fork does not come off glaciers as the other two forks and is therefore warmer, which allows for actually being in the water, at least in the summer months . This slowness and lack of turbidity is also why the Nooksack Indians referred to this fork as “always clear water.”

South Fork slowly meandering toward its meeting with the main stream

South Fork on the right, enters the main stream to form the Nooksack River proper

in the foreground as it has carved out the Nooksack Valley.

The Nooksack to the Delta and the Bay

From the South fork confluence, it is just 17 miles from Bellingham Bay as the crow flies but the river takes a circuitous route that wends itself another 35 miles to get to the bay. That course heads north, nearly to the Canadian border before turning west toward the Salish Sea and finally south where empties into Bellingham Bay. This last 35 miles cuts through highly fertile agricultural lands where the main industries are raspberry, strawberry and blueberry farming and dairy farming.

This last segment will foreshadow the topic to be addressed in Part 2 of this series in which I will present the past, present and potential harms that endanger this river and its precious denizens, the salmonids. The salmon’s fate is not theirs alone. Their fate in turn, is critical to sustaining our other aquatic icon, the resident orca pods of the Salish Sea.

Dairy farms line the river’s edge, just behind the trees for much of the last 35 miles of the river to its delta

‘

‘

The final leg of the journey as the Nooksack moseys toward the bay, just beyond the trees

The several channels of Nooksack River delta empty into Bellingham Bay and are referred to by the Nooksack tribe as “the place of many arms.”

The Nooksack River joins Bellingham Bay in the center ground after its 75 mile journey from the Mount Baker Wilderness, seen in the background with the Twin Sister peaks on the right. The Bay here is at low tide, exposing the Lummi Indian Reservation oyster and clam beds in the foreground.

Another view of the Nooksack’s mouth from the Lummi Reservation looking east across the Bay. Bellingham and the foothills are in center ground with the river’s source in Mt. Baker and the Sisters. Mt. Shuksan is obscured by Baker.

Followup — Part II

There will eventually be a followup Bucket to describe the numerous efforts to preserve, sustain and restore this marvelous river that is the natural habitat for organisms large and small from single cells to larger invertebrates to salmon, bears, deer, elk, eagles, cougars and many more critters. All of these animals are in some measure dependent on the river as well as interdependent on each other. At the top of the food chain in the Salish Sea into which its waters flow, there are our local Resident Orca. These orca are sustained by salmon, many of which are spawned and reared in the Nooksack River and its tributaries. To the extent that salmon numbers decline in the Nooksack, the Orca have less food available in the Salish Sea. Hence, the health of this river and others like it, is critical to the survival of the Orca whose numbers are seriously declining.

The relatively good news is that a large number of County, State, Tribal and Federal agencies and NGOs are actively (almost frantically) engaged in maintaining and preserving this river.

I’ll address these issues in Part 2.

Thanks, RonK!

Thanks JanF. I hope people enjoy it.

Thank you for the guided tour. And for the hope brought in that so many groups are working together to preserve the river. {{{HUGS}}}

Thanks Bfitz,

Much work in going into the preservation of this lovely and important river.