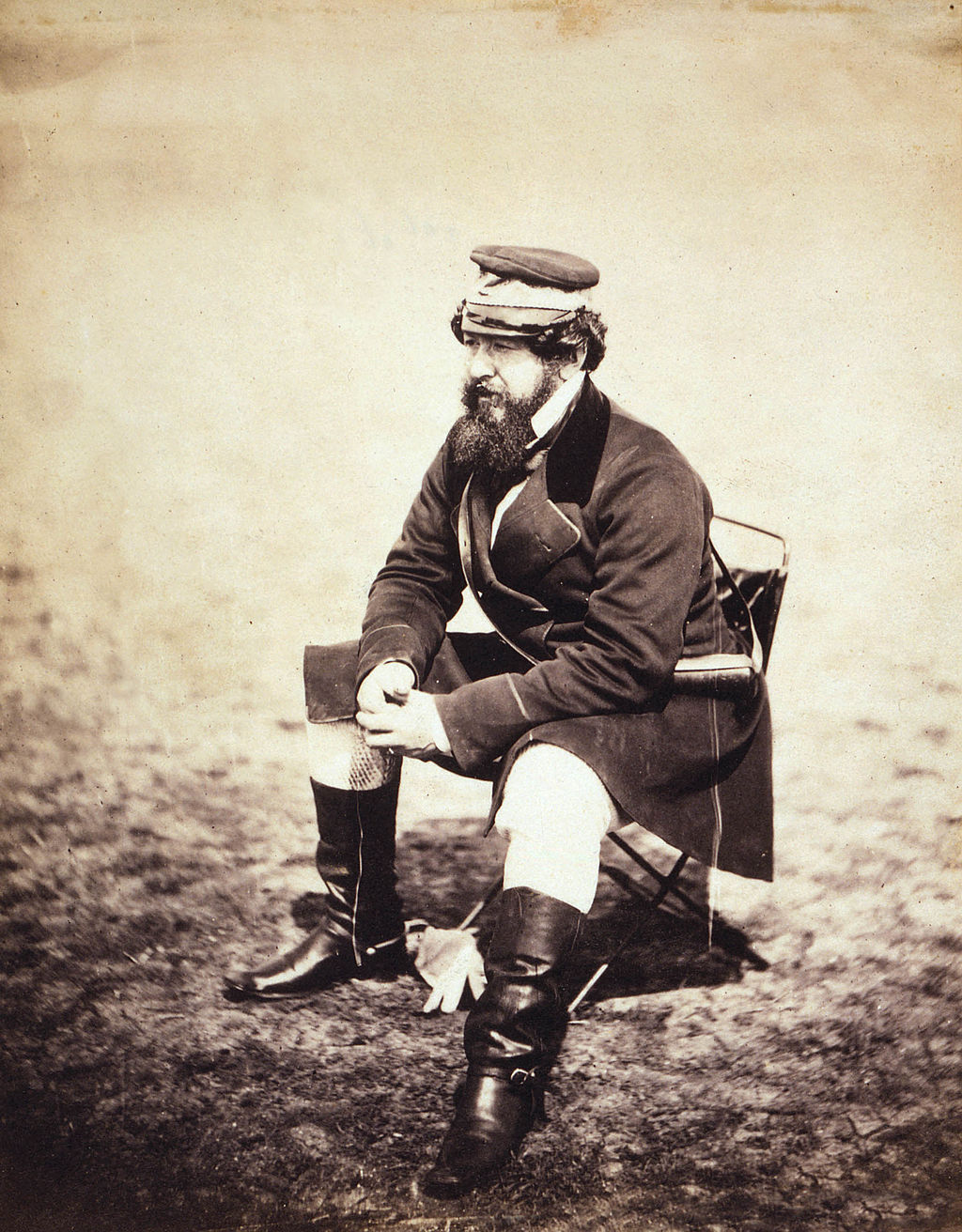

![Roger Fenton [Public domain]](https://www.motleymoose.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1024px-Williamhowardrussell-234x300.jpg)

March 29, 1861 (the Civil War started April 12, 1861) and a description of an oligarchic New York City:

We are accustomed to think the Americans a very excitable people; their personal conflicts, their rapid transitions of feeling, the accounts of their public demonstrations, their energetic expressions, their love of popular assemblies, and the cultivation of the arts, which excite their passions, are favorable to that notion. But New York seems full of divine calm and human phlegm. A panic in Wall Street would, doubtless, create greater external disturbance than seemed to me to exist in its streets and pleasant mansions. …If Rome be burning, there are hundreds of noble Romans fiddling away in the Fifth Avenue, and in its dependencies, quite satisfied that they cannot join any of the fire companies, and that they are not responsible for the deeds of the “Nero” or “anti-Nero” who applied the torch. They marry, and are given in marriage; they attend their favorite theatres, dramatic or devotional, as the case may be, in the very best coats or bonnets; they eat the largest oysters, drink the best wines, and enjoy the many goods the gods provide them, unmoved by the daily announcement that Fort Sumter is evacuated, that the South is arming, and the Morrill tariff is ruining the trade of the country. And, as they say, “What can we do?” (Letter I)

April 21, 1861 and a description of the Charleston militias/oligarchy:

The men run very large down here. Nothing, indeed, can be more obvious when one looks at the full-grown, healthy, handsome race which develops itself in the streets, in the bar-rooms, and in the hotel halls, than the error of the argument, which is mainly used by the Carolinians themselves, that white men cannot thrive in their State. In limb, figure, height, weight, they are equal to any people I have ever seen, and their features are very regular and pronounced. …Some of this superiority is due to the fact that the bulk of the white population here are in all but name aristocrats or rather oligarchs. The State is but a gigantic Sparta, in which the helotry are marked by an indelible difference of color and race from the masters. The white population, which is not land and slaveholding and agricultural, is very small and very insignificant. The masters enjoy every advantage which can conduce to the physical excellence of a people, and to the cultivation of the graces and accomplishments of life, even though they are rather disposed to neglect purely intellectual enjoyments and tastes. Many of those who serve in the ranks are men worth from £5,000 to £10,000 a year—at least, so I was told—and men were pointed out to me who were said to be worth far more. One private feeds his company on French pâtés and Madeira, another provides his comrades with unlimited champagne, most grateful on the arid sand-hill; a third, with a more soldierly view to their permanent rather than occasional efficiency, purchases for the men of his “guard” a complete equipment of Enfield rifles. How long the zeal and resources of these gentlemen will last it may not be easy to say. (Letter V)

April 30, 1861 and Southerners on England:

NOTHING I could say can be worth one fact which has forced itself upon my mind in reference to the sentiments which prevail among the gentlemen of this State. I have been among them several days. I have visited their plantations, I have conversed with them freely and fully, and I have enjoyed that frank, courteous, and graceful intercourse which constitutes an irresistible charm of their society. From all quarters have come to my ears the echoes of the same voice; it may be feigned, but there is no discord in the note, and it sounds in wonderful strength and monotony all over the country. Shades of George III., of North, of Johnson, of all who contended against the great rebellion which tore these colonies from England, can you hear the chorus which rings through the State of Marion, Sumter, and Pinckney, and not clap your ghostly hands in triumph? That voice says, “If we could only get one of the Royal race of England to rule over us, we should be content.” Let there be no misconception on this point. That sentiment, varied in a hundred ways, has been repeated to me over and over again. There is a general admission that the means to such an end are wanting, and that the desire cannot be gratified. But the admiration for monarchical institutions on the English model, for privileged classes, and for a landed aristocracy and gentry, is undisguised and apparently genuine. With the pride of having achieved their independence is mingled in the South Carolinians’ hearts a strange regret at the result and consequences, and many are they who “would go back to-morrow if we could.” (Letter VI)

April 30, 1861 and explaining the southern view of the North:

Assuredly the New England demon who has been persecuting the South until its intolerable cruelty and insolence forced her, in a spasm of agony, to rend her chains asunder. The New Englander must have something to persecute, and as he has hunted down all his Indians, burnt all his witches, and persecuted all his opponents to the death, he invented Abolitionism as the sole resource left to him for the gratification of his favorite passion. Next to this motive principle is his desire to make money dishonestly, trickily, meanly, and shabbily. He has acted on it in all his relations with the South, and has cheated and plundered her in all his dealings by villainous tariffs. If one objects that the South must have been a party to this, because her boast is that her statesmen have ruled the Government of the country, you are told that the South yielded out of pure good nature. …South Carolina was the mooring ground in which it found the surest hold. The doctrine of State Rights was her salvation, and the fiercer the storm raged against her—the more stoutly demagogy, immigrant preponderance, and the blasts of universal suffrage bore down on her, threatening to sweep away the vested interests of the South in her right to govern the States—the greater was her confidence and the more resolutely she held on her cable. The North attracted “hordes of ignorant Germans and Irish,” and the scum of Europe, while the South repelled them. The industry, the capital of the North increased with enormous rapidity, under the influence of cheap labor and manufacturing ingenuity and enterprise, in the villages which swelled into towns, and the towns which became cities, under the unenvious eye of the South. She, on the contrary, toiled on slowly, clearing forests and draining swamps to find new cotton-grounds and rice-fields, for the employment of her only industry and for the development of her only capital—“involuntary labor.” The tide of immigration waxed stronger, and by degrees she saw the districts into which she claimed the right to introduce that capital closed against her, and occupied by free labor. The doctrine of squatter “sovereignty,” and the force of hostile tariffs, which placed a heavy duty on the very articles which the South most required, completed the measure of injuries to which she was subjected, and the spirit of discontent found vent in fiery debate, in personal insults, and in acrimonious speaking and writing, which increased in intensity in proportion as the Abolition movement, and the contest between the Federal principle and State Rights, became more vehement. (Letter VI)

April 30, 1861 and identifying an inherent weakness for the South as war commences:

In my next letter I shall give a brief account of a visit to some of the planters, as far as it can be made consistent with the obligations which the rites and rights of hospitality impose on the guest as well as upon the host. These gentlemen are well-bred, courteous, and hospitable. A genuine aristocracy, they have time to cultivate their minds, to apply themselves to politics and the guidance of public affairs. They travel and read, love field sports, racing, shooting, hunting and fishing, are bold horsemen, and good shots. But, after all, their State is a modern Sparta—an aristocracy resting on a helotry, and with nothing else to rest upon. Although they profess (and I believe, indeed, sincerely) to hold opinions in opposition to the opening of the slave trade, it is nevertheless true that the clause in the Constitution of the Confederate States which prohibited the importation of negroes was especially and energetically resisted by them, because, as they say, it seemed to be an admission that slavery was in itself an evil and a wrong. Their whole system rests on slavery, and as such they defend it. They entertain very exaggerated ideas of the military strength of their little community, although one may do full justice to its military spirit. Out of their whole population they cannot reckon more than 60,000 adult men by any arithmetic, and as there are nearly 30,000 plantations which must be, according to law, superintended by white men, a considerable number of these adults cannot be spared from the State for service in the open field. The planters boast that they can raise their crops without any inconvenience by the labor of their negroes, and they seem confident that the negroes will work without superintendence. But the experiment is rather dangerous, and it will only be tried in the last extremity. (Letter VI)

I’m only halfway through the dispatches of Russell, so I’m going to continue this next week. Russell was a seasoned foreign correspondent, a world traveler, and a mostly-dispassionate observer. It’s for precisely those reasons that reading his work is important. Although The Times was generally considered to be pro-Confederacy, Russell wrote for his readers, not his editors. The documents have not been filtered through the Daughters of the Confederacy to create the myth of the Lost Cause. This is history unvarnished. This is our history, and I defy anyone to not see the profound, ongoing impact that our “original sin” is still having today.

{{{DoReMI}}} – the gentleman seems to be both an objective observer and very biased in favor of the South. Rather an interesting feat to pull off. He does have a point about the New Englanders’ need for somebody to oppress – and in some cases exterminate – but my personal opinion is that inviting in the “scum of Europe” had diluted that particular impulse by the 1860s. Sort of. Except in the case of continuing to work on exterminating Natives. sigh.

Totally a good primary source. And while I’d like to slap him for some of his pro-Confederate stuff, he isn’t filtered by the mythos and that’s very good indeed. Thank you for your continued research. moar {{{HUGS}}}

He’s not pro-southern at all; what appears to be that way is his description of how southerners viewed things. I’m guilty of not making that more clear. I’m afraid in my concern for making this so long as to be unreadable, I took shortcuts which removed clarity. So when Russell writes things like this, “Assuredly the New England demon who has been persecuting the South until its intolerable cruelty and insolence forced her, in a spasm of agony, to rend her chains asunder,” he is illustrating the attitudes he has encountered, not providing his own view. As next week’s post will show (I hope!), the more time he spends in the South, the more scathing he gets.

You’re the one reading it in the original so I will take your word for it and back off. {{{HUGS}}}

I’ll provide more information in my headers next week to clarify his approach and writing style. Your observations have been very helpful; thank you.

Thank you and I hope so. They certainly aren’t intended to be otherwise. I actually wasn’t/wouldn’t be surprised that a Brit writing for a Southern-sympathizing London newspaper be very much admiring the aristocratic Southern white males & system that supported them. What surprised me was how objective an observer he was under those circumstances. I guess I should have known better. You can’t admire that system and those people and be objective about it.