In parts 1 and 2, of this series I described the Nooksack River and how it’s three forks joined from the glaciers and water sheds surrounding the Mount Baker National Forest and wilderness area. The river that used to be prime spawning waters teemed with salmon that fed the local Indians for thousands of years. About 150 years ago, these waters were dramatically changed with the arrival of settlers from the east who logged the hillsides and plowed the prairie lands. These typical settler activities deprived the waters of the cooling effects of the shoreline trees and degraded the water quality with flooding silt. The natural processes that sustained the waters historically became seriously disturbed. The waters and the fish suffered as a result in proportion to their proximity to the settlements. The upper reaches are less polluted that those closer to the farming and populations centers.

If it is imperative to save these salmon, (and I think it is) we must first return their habitat to an approximation of that in which they evolved over many thousands of years or buy them time to continue evolving to adapt to the new conditions. And since they are the primary food source of the Salish Sea’s Southern Resident Orca, their survival is imperiled too. These salmon are also an integral part of Northwest Indian culture as expressed by the late Billy Frank Jr. of the Nisqually Tribe and leader of the Indian fishing rights and salmon restoration movements:

“As the salmon disappear, so do our cultures and treaty rights. We are at a crossroads and we are running out of time.”

Ceremony of the first salmon at Lummi Nation Attribution: flickr commons

And this is not to mention the commercial and sport fishing industries which amount to over two billion dollars a year to the State economy.

In part 3, I will describe some of the monumental efforts being put forth on behalf of these fish. Although a great deal is being done to save this fish habitat, it still begs the questions: Is it enough? Can it succeed? Following I will illustrate some of what is being done to address the problems laid out in Part 2. By necessity the coverage will be selective as there are too many needs, programs and projects to cover here.

Who is involved in this great rehab project?

Below are some of agencies and organizations involved in the efforts on the Nooksack. I will refer to most of them along the way.

Treaty Tribes of Western Washington: (local Tribes)

- The Nooksack — Department o Natural Resources,

- Lummi Indian Tribe Department of natural resources

Federal Agencies:

- EPA, National Forest Service, National fisheries, Department of Interior, Americorps

State of Washington:

- Departments of Transportation, Ecology, Fish and Wildlife, Salmon Recovery Funding Board

Local Environmental Educational programs:

- Western Washington University, Huxley College of the Environment

- Whatcom Community College environmental studies

- Bellingham Tech College: Fisheries studies

- Northwest Indian College

Whatcom County several agencies such as: Whatcom Watersheds Information Network (WWIN)

Non-Governmental Organizations:

Now that is a lot of groups working on and in this one river and there are more groups and more rivers. It is encouraging to see how many agencies are working on this river alone.

Signs like this are posted at each the many rehab sites listing the contributors. Here there are five agencies involved including Federal, State and Northwest treaty Indians. The Skookum and Edfro are salmon spawning creeks that feed the South Fork of the Nooksack River.

Instream Restoration: Barrier Removal

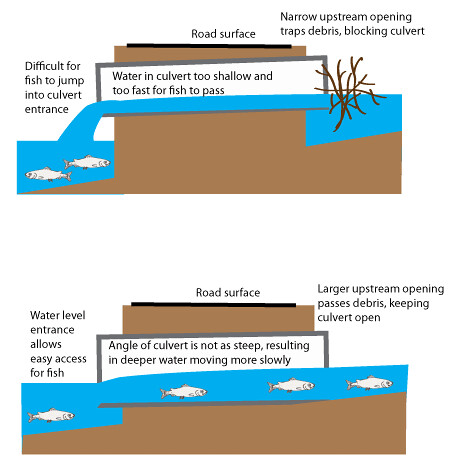

Culverts under roadways are often barriers to fish attempting to reach their spawning grounds and thus hinder the number of eggs that can be deposited and fish hatched. Although culvert removal has been an ongoing concern for the state, it is expensive and was moving forward too slowly to significantly affect increases in salmon productivity. It was agreed that the culverts must be removed but who was to foot the estimated bill of 3.7 billion dollars, the state or the feds?

The Treaty Tribes of Western Washington took the State to court over the allegation that the culverts presence violated their treaty rights to fish in their usual and accustomed places and that the culverts prevented them from to be able to earn a “moderate living” from fishing as per the treaty.

Then the question arose of who was to pay for the removal? The tribes won their suits against the State at all levels which were eventually appealed up to the Supreme Court. Just this year a SCOTUS tie sent the suit back to the Ninth District Court that had already ruled in favor of the tribes. The state had to pay for culvert removal.:

In a series of treaties, the federal government promised northwest Indian tribes “[t]he right of taking fish, at all usual and accustomed grounds and stations . . . in common with all citizens.” This Court has held that this language guarantees the tribes “a fair share of the available fish,” meaning fifty percent of each salmon run, revised downward “if tribal needs may be satisfied by a lesser amount.”

About 1,000 culverts and related barriers for salmon and steelhead trout must be replaced. According to the court, 90% have to be removed by 2030.

Depicted in the photos below is an example of one excellent repair of a salmon barrier that I wrote about earlier. In this project, the Department of Transportation “daylighted” a salmon spawning creek that had been buried for 120 years and ran through a half mile brick culvert system and road crossing culverts as shown.

Before, during and after restoration:

A culvert leading to the undergrounding of the creek. Now gone.

The daylighted creek with new seedlings planted along the riparian corridor.

The same creek, photo taken from the identical spot as above, 3 years later. The shade will cool the water and deciduous leaves and vegetation will help nourish the stream. Salmon like it already.

This stream rehabilitation process is ongoing throughout the Nooksack watershed and the state as a whole. It has to help somewhat.

Habitat Corridors Restoration

A second focus for salmon restoration is returning the riparian corridor along the waterways to its original state. This restoration is essential to providing salmon with the environment they need to spawn and for their young to mature as they grow and prepare to go to sea.

Riparian corridors along the river and its tributaries were largely destroyed as settlers moved in and cleared the flatland forests for farms along the rivers and streams. Further, hillsides were denuded for the plentiful and prime Douglas-fir, Western Red Cedar and other trees for building materials. Having uprooted and stripped the trees and native undergrowth, the prolific rains washed the unsecured soils into the rivers which often then overflowed. This flooding washed out previously natural barriers which provided pools and slow water for spawning areas. In addition the bared river banks provided no protection from summer sun which raised water temperatures to unsafe levels for the fish.

These river banks and adjoining riparian areas are now the prime target for stream rehabilitation. Land clearing and logging regulations have slowed this degradation but much remains to be rebuilt. Local NGOs have taken up the task with assistance from state and federal support to replant these areas along the Nooksack.

Information kiosks and snack tents at a habitat restoration work site

Two of the local players in the rehab process are the Nooksack Salmon Enhancement Association (NSEA) and The Whatcom Land Trust which often team up with their respective volunteer crews. All native vegetation planted by these groups is grown at NSEA’s nursery.

On December 1, My son and I went with these two NGOs as part of an ongoing job replanting of native fir, cedar, and various shrub and berry plants.

Two days before our work party, rains in the mountains to the east rose to flood levels and with little to secure the river banks, between 4 and 5 feet were eroded into where we had intended to plant, highlighting the very problem that we were trying to deal with. So, we just moved our planting area further inland.

.The undercut river bank where several feet were lost in the days before our work party.

While this replanting is going well and there have been hundreds of volunteers of all ages willing to come out on cold and foggy mornings, the task is enormous. This was my second planting trip to this specific property and both were well attended and successful in planting all the plants intended.

A planting of 500 trees along this short stretch is but a drop in the bucket. But we persist. More are scheduled along this strip of the river and on all other areas to which we have title and access that impinge on this river and its spawning tributaries.

Agriculture — Salmon Compatibility

Cooperation: Certain agricultural practices are incompatible with keeping a river habitable for fish and other aquatic critters. Specifically, significant steps must be taken to ameliorate farm pollution from runoff and seepage of fertilizers and animal manure. This runoff has been an ongoing problem for the Nooksack River with its three forks and for the shellfish tidelands into which the river empties. A Water Improvement Plan is in place to help ameliorate these issues but it is difficult to implement.

This farm run off situation has created a controversy over the years between farmers and environmentalists, tribes and commercial fishers intent on saving the salmon. That conflict seems to be abating somewhat as we are seeing some simple cooperation between the sides and modern farm processing technology is being introduced.

Throughout the county a series of small creeks that are historical salmon spawning streams still run through the farm country. Most of these have been straightened, dredged, swamped, and blocked at various times. Since they run through and by fields their riparian habitats are compromised and they collect runoff water that drains into the Nooksack and ultimately into the Salish Sea. Since they run along or through farms, their riparian areas are denuded except for canary grass, right down to the water’s edge. Although there is a county Water Improvement Plan in effect for these creeks, much remains to be done concerning its effectiveness in preserving these waters and the fish.

One of these, Double Ditch Creek still supports two endangered salmonids (Steelhead trout and Chinook salmon) along with the four other salmon species and various trout. Double Ditch creek is split into two branches, one on either side of the road with a farm on the other side of each. The ditches flow south from Canada and into our county. Just this past summer a beaver dam north of the border blocked the flow of one branch of Double Ditch killing thousands of small fry salmon and trout and threatening to kill them all.

State biologist net stranded salmonids to transfer them to the other stream.

This crisis was spotted by local dairy farmers who called the Department of Fish and Wildlife officials for help. The biologists told the farmers that if the fish could get some cool water they could last until and biologists could get there to deal with the problem. The farmers diverted their irrigation pumps from their crops into the ditch until the following day. When the biologists arrived, they netted the salmon in the low water ditch and moved them across the road into the other ditch, saving those that remained.

Although this is a good sign of the willingness to work together to save the fish, the fact remains that these ditches run through and by dairy farms and berry fields and carry their runoff to the river and on to the bay. There is more to be done.

Technology: This brings us to a second relatively bright spot for fish stream restoration and maintenance. In this case it comes from technology applied to dairy farming, an industry that has traditionally been one of greatest polluters of waterways in our area. This technology along with farmers’ cooperation is coming to the rescue of the Nooksack’s manure and seepage ills.

I recently took a tour of a family farm that has installed state-of-the-art technology at their dairy farm along the South Fork of the Nooksack. (Although the application of this technology is new and revolutionary here, it is mandated for farms in Western Europe.)

The technology involves anaerobic digesters and nanofiltration that transform farm waste (manure) into reusable products that go back into the farm and do not harm the environment. This equipment was purchased in part with the assistance from a Washington State Conservation Commission grant to demonstration the economic feasibility of the technology on a family owned dairy farm.

Coldstream Farms will be the first farm in the state to use this full process which is shown below.

First manure is pumped into a holding pond. From there it is fed into the “beddingmaster” filtration process which produces a soft fluffy substance that becomes clean bedding material for the cows.

From there other filtration processes (nanofiltration and reverse osmosis) continue to produce useful products as shown in the jars in the photo below.

Engineer explaining the manure filtration processes and its products

From the beddingmaster the liquid that remains is a mucky liquid shown in the left jar . An emulsifier is then introduced that separates most of solids from the liquid as seen in jar 2. The solids from this become the pile of brown material in the center which is a solid fertilizer, rich in nitrogen and phosphorous and used on the farm or could be sold to other farmers. The remaining liquid in the third jar can also be used as fertilizer to be spread on the fields or put through a final process of nanofiltration that completely purifies the liquid into useable water – the jar on the right. This water could be drunk by the cows, used for various farm cleanup tasks or be pumped back into the river at times of critically low water. Technology is now clearly present to nearly eliminate farm waste as a river pollutant. What is left is to demonstrate its economic viability and or incentives to farmers to adopt it. We were informed that some of the local dairy farmers were resistant to this new technology and wanted no one to tell them how to run their dairies. This is yet another hurdle.

Are more salmon hatcheries the solution?

Salmon just beginning to hatch at a Hatchery.

The Fish Hatchery:

Another route to bringing the fish back is to raise more fish in hatcheries and release them into the rivers as our state has been doing since 1895. Although this sounds like a logical solution it is actually quite controversial. I have written on this before and won’t go into it again in any detail except to say that we’ve been rearing salmon by the many millions each year and releasing them into the rivers where they head to the sea for several years before they return to spawn. For example in 2013, 73 million salmon were released by the State of Washington hatcheries and now it is probably closer to 100 million. At this point the hatchery salmon far exceed the native or wild salmon as 75% of salmon caught in Puget Sound are hatchery fish. (90% of those caught in the Columbia River are hatchery fish.) There are now about 66 state run salmon hatcheries and 51 tribal hatcheries in the state. With putting all of these fish into the salt water they are still are not increasing the overall fish returns. And worse, the hatchery fish might even be harming the native salmon.

There is much more to saving the salmon than putting more into the water and improving their habitat, both of which are critically important. Other issues are afoot as illustrated by the fact the percentage of released salmon that return has dropped to just 1 in 100 from 3 per 100, 40 years ago. Many factors likely contribute to this decline in addition to local factors such as warmer ocean temps, more predators in their estuaries, at sea and on return. It is also thought that the hatchery fish might not be as hardy as the wild fish.

All of this is not say that there are no more fish. In some places there are lots and many make it back to spawn at the hatcheries from which they were released. Below is a video at Kendall Creek, a Nooksack tributary adjacent to a state fish hatchery. The salmon shown here are Chum and Coho, having returned by the hundreds waiting to spawn or being hatchery fish, they will be caught and their eggs harvested for the hatchery. Notice how they tend to stay close to the shore with the overhanging vegetation.

An Assessment of the Future of Salmon in the Nooksack and the Salish Sea

A great deal of effort and money is being expended by numerous agencies at all levels of government and there are signs of cooperation between government agencies, environmentalists and farmers.

One of the major stakeholders in our salmon stocks along the river and for all of Puget Sound and the Salish Sea are the Treaty Indian Tribes of Western Washington whose lives, livelihoods and culture depend on these resources. They note as have others that over the past 40 years, much money has been spent, habitat restored, cuts made to fishing harvest along with increases in hatcheries output and still the numbers of fish go down. These groups have recently announced that they will institute their own historic strategy they call: “Gwadzadad” in Lushootseed language, (a Puget Sound/Salish language group spoken by NW Indians), meaning “the Teachings of our Ancestors.”

It is a unified tribal habitat strategy designed to organize and focus work around key habitats and shared goals necessary to protect tribal treaty rights and resources. It aims to preserve and restore the natural functions and connectivity of our river, marine and upland ecosystems, and to seek accountability for decisions on the use of our lands and waters.

As noted in Part 2, to save the salmon we must save their habitat and that is where much of the effort is focused. Certainly progress is being made with restoring streamside vegetation and reducing polluting farming practices. Hatcheries raise and release millions of salmon each year. Even if we largely reestablish the habitats for salmon to spawn, grow and return, the fact remains that the largest part of their life cycle is spent in the ocean where conditions are not always favorable. Only one of a salmon’s 2 to 4 years is spent in these streams before they head to sea.

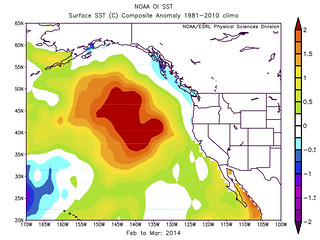

There are other obstacles to salmon’s future success such as the Blob. In late 2013, a large mass of warm water dubbed the Blob, appeared over the north pacific and Gulf of Alaska and persisted into 2016. This is where the salmon congregate for a couple of years as they mature before returning to their natal streams to spawn.

This temperature anomaly has affected zooplankton in the north pacific – the stuff that salmon feed and grow on. There were lasting effects of the blob evidenced on the recent salmon returns. Until a couple of months ago, we were hopeful that it was gone for good. But recently it has reared its ugly head again as “Son of the Blob.” How long this one will last is unknown. Its effect on salmon will not be good but how bad is still unknown.

Son of Blob warming the waters of the

North Pacific and Gulf of Alaska

The final non-stream factor I’ll mention affecting salmon is that the seal and sea lion population eats 22 % of smolts (young salmon preparing to go to sea) before they even get out of Puget Sound. Prior to the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, fishermen shot these mammals on sight. Following their protection 46 years ago, the Puget Sound seal population has grown to become the most dense in the world. Now that’s a tough one to deal with.

However, just this month Congress has amended the Marine Mammal Protection Act with the support of the states of Washington, Oregon and Idaho along with the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission to allow controlled killing of sea lions in the columbia River as a means of salmon protection.

There are bright spots and there are obstacles to rehabilitating the salmon runs to approximate those of yesteryear. Should we be optimistic? My optimism is buoyed by the numbers of people and agencies that take this problem seriously and devote their time and money to fixing it. However, that optimism is tempered by the large scale negatives that seem to be beyond our immediate control such as the increasing effects of climate change which is already affecting our watersheds, ocean acidity, the blob, and the sheer number of these issues.

According to our latest State of Salmon Report “…the legislature has allocated $179 million to salmon recovery projects since 2007, but that hefty sum is about 15% of what is needed.”

My view is very much in keeping with that of one of our own here along the Nooksack River, a retired biologist who continues to work on saving the salmon:

“Overall, Puget Sound is not improving,” Beatty said.

Asked if he was optimistic that salmon recovery efforts will succeed, Beatty replied, “Yes, one should be optimistic if the human element can get it together, but that hasn’t completely happened. Unless we have that, no – you can’t be optimistic.”

So there you have it. My own take on the future of the salmon would be a cautious optimism recognizing that there is a long way to go and many uncontrolled variables. The primary concern from my perspective is whether we can get our acts together, locally and globally to save the planet, all the fishes in the ocean and the Nooksack River.

Thank you for this. And for your work as part of the restoration. I’m not particularly optimistic but am firmly of the opinion that we have to try because we certainly won’t succeed if we don’t. Thank you again. {{{HUGS}}}

Thanks Bfitz.

The optimism is guarded but we need to keep plugging away, just in case we can do some good.

Thanks, RonK! I hope this project is successful. It seems like a giant doomsday clock is ticking on irreplaceable habitat – it is not enough to say “we must fix this”, we have to actually do the fixing.