He took theology out of white western Europe and created a new theology to, for, and by black America.

…the God of the oppressed takes sides with the black community. God is not color-blind in the black-white struggle, but has made an unqualified identification with blacks. This means that the movement for black liberation is the very work of God, effecting God’s will among men. (A Black Theology of Liberation, p. 6)

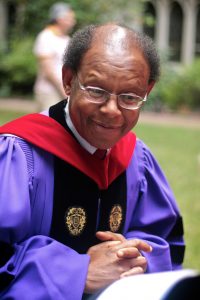

He was the [self-described] “angriest theologian in America.”

By the summer of 1968, I could no longer contain my rage. I was extremely angry with white churches and their theologians who were contending that black power was the sin of black pride and thus the opposite of the gospel. Since white theologians and preachers wrote most of the books in religion and theology, they had a great deal of power in controlling the public meaning of the gospel. During my six years of graduate work at Garrett and Northwestern, not one book written by a black person was used as required reading. Does this not suggest that only whites know what theology and the gospel are? The implication of that question consumed my whole being. I had to write Black Theology and Black Power in order to set myself free from the bondage of white theology. (The gospel and the liberation of the poor)

He had a moment…

In the late 1960s, Cone later recalled, “I was within inches of leaving the Christian faith.” He had spent a decade immersed in theology — poring over the teachings of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, studying for a doctorate and closely following the sermons and speeches of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., whose nonviolent civil rights tactics were informed by his ministry. Then he heard Malcolm X.

The Black Power leader proclaimed that “Christianity is the white man’s religion,” one that encouraged African Americans to wait patiently for a “milk and honey” heaven, and called for blacks to fight for their rights “by any means necessary.” His assassination in 1965, followed by the killing of King three years later and the ensuing Detroit uprising of 1967, plunged Cone into what he described as a full-fledged spiritual crisis.

“He was a Christian theologian,” said Christopher Momany, Adrian College chaplain, “but angry that white America had domesticated the gospel for racist purposes.”

To gather his thoughts, he traveled to Little Rock and all but locked himself inside the church office of his older brother, a fellow minister. Six weeks later, he emerged with a new perspective, dubbed black liberation theology, that sought to reconcile the fiery cultural criticism of Malcolm X with the Christian message of King. (Former Adrian College professor, author remembered

…it became a movement.

James Cone not only opened the door to liberation theology but showed the message of liberation to be at the core of the gospel. Cone’s black liberation theology, then Gustavo Gutierrez’s Liberation Theology, then other indigenous versions of that in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, then women’s, then womanist theologies, have opened up an understanding of God that is not controlled by white Western men (even helping to set many of them/us free). (Why James Cone Was the Most Important Theologian of His Time)

What was radical in 1969 should not be in 2019, and yet…

Cone’s theology isn’t all that hard to understand, and it’s not even that hard for a liberal mainline Protestant to agree with in today’s #BlackLivesMatter world. But Cone’s challenge to white Christians isn’t to get us to agree with his theology. It’s far more radical than that. As he puts it in God of the Oppressed, “God has chosen what is black in America to shame the whites. . . . The divine election of the oppressed means that black people are given the power of judgment over the high and mighty whites.” What Cone is calling for on the part of white Christians is much more difficult: sacrifice, the tearing down of our values, the relinquishment of the comfort that our sociopolitical significance affords us. He writes:

While divine reconciliation, for oppressed blacks, is connected with the joy of liberation from the controlling power of white people, for whites divine reconciliation is connected with God’s wrathful destruction of white values. Everything that white oppressors hold dear is now placed under the judgment of Jesus’ cross.

Nothing about this should be easy. (James Cone’s theology is easy to like and hard to live)

James Cone opened my eyes to a world that, in my bubble and in my privilege, I had never considered. Almost a year after his death, I find myself still reading his words, still learning, and still struggling with their impact. None of this is easy, but life would be so much harder without his insights.

{{{DoReMI}}} – since my first reaction to reading this (at least the last few paragraphs) was “not me” it seems I really needed to read it – and to start working on it. I don’t know what “white values” I hold that need to be destroyed but I’d best get busy finding them. I obviously have some or I wouldn’t have reacted that way. The problem being that they aren’t obvious to me. So. To work. Very much yes James Cone’s theology is easy to like and I very much like it. Now to find the “hard to live” part that is being hard for me – and deal with it.

When I first read James Cone before I was even 21, it was my first experience of unmasked black anger. It was painful and shocking and hurtful…and whenever I start feeling the hubris that says I’m as “woke” as I need to be, I go back to those feelings and am immediately humbled. I will say this about Cone…he clearly communicated his anger at whitey (his word) and his desire for the black community to celebrate blackness, but I never, ever felt as if he was motivated by hate. Instead, he points to the righteousness of a god of liberation as the starting point for his views.

I don’t remember exactly when the anger became real to me. My mother was always outraged at how Black folks were treated – especially in the South with the obvious Jim Crow and legal segregation – so I sort of grew up with it. My mother equally did not believe in the white Xtianity that smugly said god created whites as supreme and everybody else was not only inferior but were created to support white folks in their superiority. She was a “fan” of Malcolm X as well as MLK, loved James Baldwin’s writing, read newspapers that were still keeping track of lynchings…and so I got a lot of stuff at so very young an age I’m not sure when or how I got it. Which is part of my problem in digging out what I didn’t get but think I did. sigh. One of the things Momma taught me was a very useful version of the Golden Rule – If it’s wrong when it’s done to you, it’s wrong when it’s done to others & it’s especially wrong for you to do to others – that one has shined a light on my own blind spots more than once. I’ll never claim to be “woke” – like ally, it’s not a claim for me to make but an award so to speak to be granted me by others should I ever earn it. Outrage and righteous indignation are not hate. They are the basis for any liberation theology – no matter how uncomfortable it makes me feel. And that it makes me feel uncomfortable tells me there’s stuff to root out.