![Photograph scan created by Arizona Historical Society; AHS location information: Pictures-Places-Bisbee-Bisbee Deportation, #43171. Original photographer and publisher not known. [Public domain]](https://www.motleymoose.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Bisbee_deportation_guns.jpg)

In July 1917, the United States had been officially involved in WWI for three months. Entry into the war came after several years of highly-popular neutrality; although Germany was not particularly admired in the United States, the desire to maintain isolation was stronger. However, with the German decision to engage in unrestricted submarine warfare, which led to the sinking of American merchant ships, and the release of the intercepted Zimmerman Telegram (where Germany offered to help Mexico regain lands lost in the Mexican-American War), Americans were largely supportive when President Wilson asked for and received a declaration of war in April 1917.

In July 1917, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW with members called the Wobblies) were at their peak of membership. The IWW was unique in its style of organizing: a general union that also organized workers within their industry (as opposed to unions which limited their organizing to a specific industry). In addition, the IWW was more radical than many unions and maintained ties with socialist and anarchist labor movements.

In July 1917, mining had been the center of the economy in Bisbee, AZ for several decades, and Phelps Dodge Corporation, which had acquired the Copper Queen Mine, was a leading copper mining company with mines of unusually high-grade copper. In a country recently at war, the need for copper took on new urgency. Copper had long been a critical element in manufacturing, but it was now needed in greater quantity for munitions industries. The owners of Phelps Dodge embraced the new jingoism of an America at war and viewed their contribution of copper as both profitable and patriotic.

It was in this climate that the Bisbee Deportation of 1917 occurred. Despite living in segregated mining camps and company towns (and being paid different rates of pay, depending on one’s perceived ethnicity), the newly-organized IWW Local 800 called for a strike if the Phelps Dodge mine owners didn’t meet their demands. The workers were demanding safety improvements (e.g. the end to blasting while workers were in the mines) and payment of wages in U.S. dollars rather than company scrip. Phelps Dodge rejected every single one of the demands, and when the miners went on strike on June 26, 1917, other miners in the area walked out too. It is estimated that 3000 miners, or about 85% of the mining workforce, joined the strike. (Bisbee Deportation)

The strike was peaceful, but the general manager of Phelps Dodge, Walter Douglas, was a dedicated union buster. Not only was he the son of one of the developers of the Copper Queen (and board member of Phelps Dodge), perhaps more importantly, he had recently been elected president of the American Mining Congress, an employer trade association. His platform when running for the American Mining Congress role was the promise to break every union in every mine. In Bisbee, he had created a Citizens’ Protective League (business owners and middle-class residents of Bisbee) and the Workmens’ Loyalty League (some of whom were union, but not IWW, miners). When the strike was called, local authorities, influenced, guided, and perhaps even instructed by Walter Douglas, asked that the AZ governor request federal troops to break the strike, using the wartime need for copper as their rationale. President Wilson refused, although he did appoint a former AZ governor as mediator.

After a successful, small-scale, dry run against striking IWW workers at a Phelps Dodge mine in Jerome, AZ, plans for action in Bisbee commenced.

Cochise County Sheriff Harry Wheeler and Phelps Dodge General Manager Walter Douglas secretly deputized and armed 2,200 men, dubbing them the Loyalty League. On July 12, 1917, Sheriff Wheeler issued a statement: “I have formed a sheriff’s posse of 1,200 men in Bisbee and 1,000 in Douglas, all loyal Americans, for the purpose of arresting, on charges of vagrancy, treason, and of being disturbers of the peace in Cochise County, all those strange men who have congregated here from other parts and sections for the purpose of harassing and intimidating all men who desire to pursue their daily toil…This is no labor trouble…but a direct attempt to embarrass and injure the government of the United States.” (Bisbee Deportation)

These “strange men” were not coincidentally heavily represented by immigrants: “The largest ethnic group of deportees were Mexican (229), followed by American (167), Serbian (82), Finnish (76), Irish (67), Austrian (40), Croatian (35), British (32), Montenegran (24), German (20), Swedish (18) and Dalmatian (14). Twenty-three other nationalities had single-digit numbers.” (Bisbee Deportation)

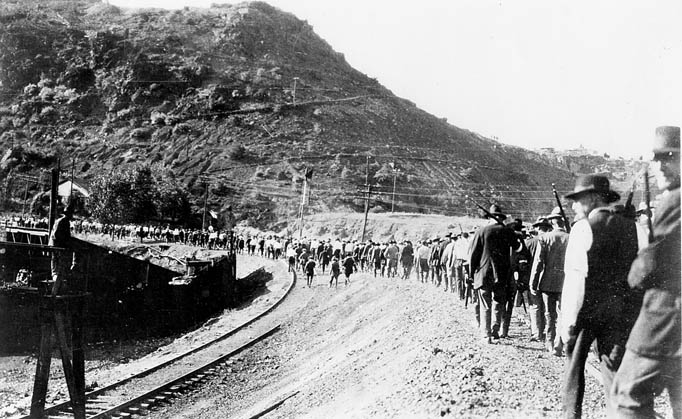

Phelps Dodge provided a list of miners, and the vigilantes did the rest. They went to miners’ homes and marched them at gunpoint to the ballpark two miles from the center of town. The posse did not confine itself to the names provided by the mining company; anyone who was known to have voiced support for the strike or for the IWW was marched to the ball field. Several grocery store owners were collected, their cash registers emptied, and goods grabbed from the shelves, and random men, with no apparent ties to the mines or the miners, were also captured. The Loyalty League had developed its own sense of rough justice and who should be incarcerated.

Phelps Dodge may not have managed to control their “deputies,” but they did control other things. During the course of the collection of strikers and afterwards, executives from Phelps Dodge shut down the telegraph and telephones and were able to prevent reporters from filing stories. In addition, it was Dodge Phelps personnel who met with executives of the El Paso and Southwestern Railroad and made arrangements for the final, planned stage of extralegal humiliation and dehumanization:

Strikers were taken to a kangaroo court in a ball field. If they promised to return to work and were vouched for by a Loyalty Leaguer they were turned loose. Twelve hundred others were taken to cattle cars and box cars, locked in without food or water in summer temperatures of 112 degrees, and “deported” across the state line to New Mexico. The Bisbee Daily Review labeled the strikers “agitators, idlers, wreckers, traitors, spies and anarchists.” (Bisbee Deportation)

What this single paragraph does not convey is the terms and conditions that were part of this effort. The local sheriff, Harry Wheeler, oversaw the proceedings in the ballpark from his car, which was mounted with a machine gun. The promise of “freedom” was only offered to those who were not IWW members. The 23 rail cars provided by El Paso and Southwestern were actual cattle cars, complete with manure, which in some cases was up to 3 inches deep. The trip took more than 16 hours to travel the 200+ miles, and when a stop was made near Douglas, AZ to finally provide water, 200 armed guards and 2 mounted machine guns were deployed to patrol the tracks. Sheriff Wheeler was so committed to his role in the deportation that he put his own brother on one of the trains. They never saw each other again.

If this were a happily ever after story, the mining company executives and their lackeys would have been prosecuted for kidnapping; the miners would have returned to their homes in Bisbee; and Phelps Dodge would have given up its union busting ways. Instead the Citizens’ Protective League established effective martial law in Bisbee, and the kangaroo courts and “deportations” continued until November 1917. Public sentiment, stirred by the war and “patriotism” criminalized the deportees, and while a few received compensation through civil suits, most lost everything they had in Bisbee and never returned. No executive was successfully prosecuted. Even though 21 mining company employees and law enforcement personnel were arrested, the charges were dropped when it was held that no federal laws had been broken. State charges were never filed. In 1983, under the leadership of Richard Moolick, Phelps Dodge finally succeeded in busting the unions (in a three year effort and with the governor of AZ, Bruce Babbitt using the National Guard to protect scabs). “As Phelps Dodge President and Chief Operating Officer in 1983, Dick Moolick made labor history by facing down striking unions at Phelps Dodge mines in Arizona and its refinery in El Paso, Texas, ultimately achieving decertification of the unions and saving the corporation from bankruptcy.” (Richard Moolick) In 2009, Moolick was inducted into the Mining Hall of Fame.

An evil society rewards evil people.

The whole story, coupled with some of the insights from the documentary, is even more sad and horrifying than my post implies. There are descendants in Bisbee today who still defend the actions taken by pointing out that the “deputies” saved Bisbee from socialists and communists. They have no idea that those are 100+ year old talking points that just get regurgitated when another form of Othering is needed.

Those talking points haven’t changed since the Russian revolution. And it was “anarchists” before that. Before that they didn’t need a reason other than “that (BIPOC) has more than I have” to deport or destroy. Which is still the reason underlying all our evil to this day.