![Ann Rosener [Public domain]](https://www.motleymoose.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Production._Willow_Run_bomber_plant._8e11142v-1024x756.jpg)

If Henry Ford had had his way, it’s quite possible Ford Motor Company would have gone out of business producing nothing more than the Model T. Fortunately for Ford (pater and company), Edsel Ford was able to persuade his father to expand the offerings of Ford; after 18 years of making the Model T alone, the Model A was introduced in 1928. The push/pull between Ford the elder and his son was an ongoing feature of their relationship, with Henry being the conservative face of Ford and Edsel being the forward-thinking president who had to fight tooth and nail to see changes happen. It was this dynamic that drove Edsel and fixed him on wanting to make his own mark and create his own legacy. At the age of 14, he tried to build his first airplane and by 1925, Ford had bought out Stout Metal Airplane Company (after an initial investment of $2000, made at the urging of Edsel). The Fords had already built the first concrete runway and the first airport hotel; now they were making airplanes in the factory they built. They became the top airplane-production company in the country with their “Tin Goose” being the favored plane of Hollywood starts to start-up commercial airlines like TWA and Pan Am to the U.S. military. It was that military involvement, combined with the Crash of 1929 (sales in 1929 equaled 94 planes; by 1933, only 4 planes were sold), that led to the end of the Ford involvement in the airplane industry. When the military conducted tests to see if the Tin Goose could be converted to carry bombs, an accident happened leading to the deaths of two test pilots. Henry Ford, who was a committed pacifist and uneasy about helping the military under the best of circumstances, decided to pull the plug. Henry Ford even had Ford Airport turned into a test track for cars.

With that background, it should be no surprise that the building of Willow Run did not happen easily or with the full support of Henry Ford. In May 1940, when Roosevelt asked Congress for funding for the military, he announced a goal of starting a program that would build 50,000 airplanes. By June 1940, Edsel Ford had negotiated a contract with the government for the production of airplane engines; 6000 for the English and 3000 for the U.S. Despite headlines around the world praising Ford for the contract, within two days, Henry Ford changed his mind, feeling that Roosevelt was trying to force the country into war. When a representative from Washington came to Michigan to try to persuade Henry Ford to change his mind, he only made matters worse by mentioning how happy President Roosevelt was about the original contract. Ford, who loathed Roosevelt, cancelled the entire order.

While the workers and factories of Ford Motor Company stayed on the sidelines while defense contracts were being awarded, the other automobile companies were actively winning work. Studebaker, Packard, GM, Willys, Nash, and Fisher Body all had contracts. When Edsel Ford couldn’t persuade his father to agree to any contracts, he called in other long-term Ford employees to try to persuade the elder Ford. Finally, Ford reluctantly agreed, in part because the threat of the Roosevelt administration taking over Ford in the event of war was a very real possibility. Ford agreed to take on aviation work, but for the defense of the United States only. The specific aviation work in question was to supply machine parts for the B-24 Liberator bomber, made at that time by Consolidated Aircraft. After touring the Consolidated facility, Edsel Ford came to the conclusion that the bomber was impressive, but the production practices of Consolidated were not. Within 48 hours, he was proposing to the government that Ford take over the full production of the B-24 with the promise that he would build and equip a plant that would be able to complete one Liberator per hour. Before even having a government contract, in January 1941, Edsel Ford publicly announced that he would build an airplane factory that would start production by the end of 1941.

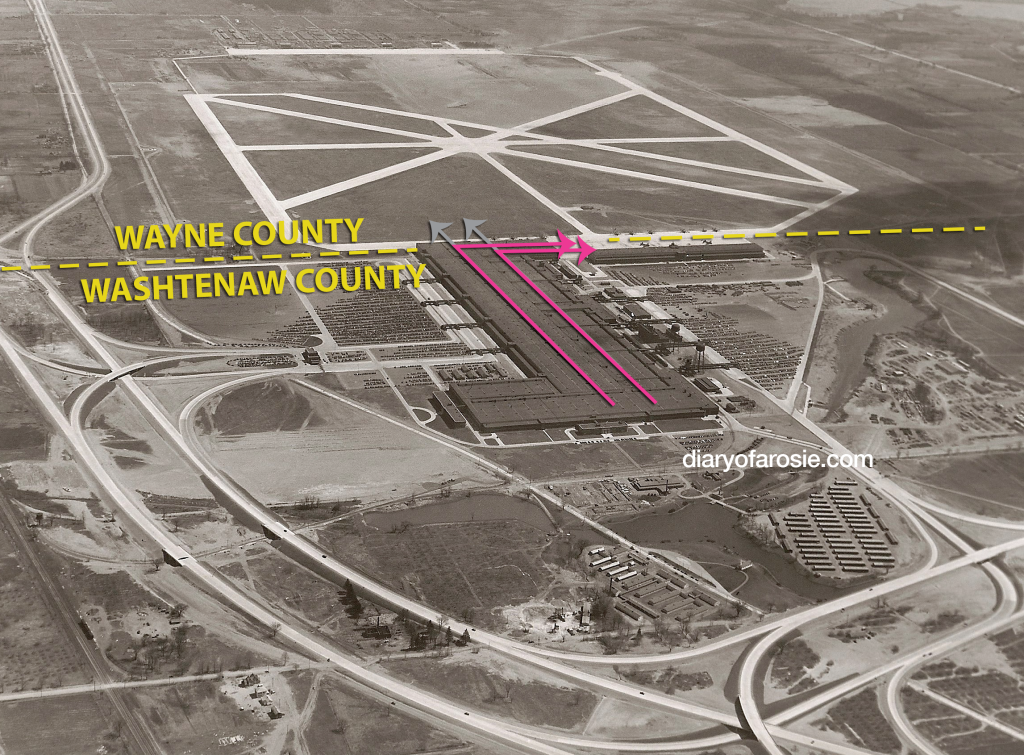

Once again, however, Edsel was at the mercy of his father’s whims. First, he had to persuade his father to donate the land, 1450 acres of farmland and an orchard owned by Henry and 27 miles west of Detroit. Noted architect Albert Kahn, who had designed the original Ford Highland Park plant, as well as the Rouge complex, was tapped to design the plant which needed to accommodate fully-assembled B-24s and 100,000 workers. The plant also needed to be designed in an L-shape to accommodate Henry Ford’s insistence that no part of the plant cross the line into Democratic Wayne County; the entire plant must be contained in Republican Washtenaw County. A special turntable had to be built to manage turning the airplanes at an additional cost of $300,000, but Henry Ford was satisfied.

In addition to the plant, runways were built; a rail spur leading directly into the plant for delivery of supplies; and even a highway extension from Detroit to Ypsilanti were built. But before the plant could produce a single airplane, there were other issues that had to be resolved: Henry Ford’s hatred of unions as enforced by his “Ford Terror” in the person of Harry Bennett; a strike at the Rouge; and Bennett’s ill-considered pitting of Black autoworkers against white autoworkers.

Next week: Edsel Ford’s intervention, the opening of Willow Run, and the future in spite of Henry Ford.

{{{DoReMI}}} – and yet the only thing “history” knows about Edsel Ford is the car he designed that didn’t sell. smh. Once upon a time I admired Henry Ford – the man I learned about in history class who never really existed. When I found out what the real man was like…nope.